Global critical mineral demand is expected to increase dramatically in coming decades, from a 7.1 million tonnes in 2020 to 42.3 million tonnes in 2050. Global commitments to decarbonisation are the main drivers of this growth, because clean-energy technologies depend on large quantities of critical minerals. But all manner of sophisticated industries, including defence manufacturing, will also compete for these materials.

Secure and reliable critical mineral supply chains will be vital for energy transition. The supply chains are the secret to scaling up installation of wind turbines, advanced batteries, electrolysers and clean-energy grids.

Southeast Asia has significant natural reserves of several key critical minerals, including nickel, tin, rare-earth elements (REEs) and bauxite, and the region is still not fully explored for more of them. But establishing downstream processing of the materials in Southeast Asia is a great challenge, especially if high environmental standards are to be met.

To turn itself into a hub of critical minerals supply, the region will need help from countries that are experienced in the field, such as Australia, India, Japan, the United States, China and European nations.

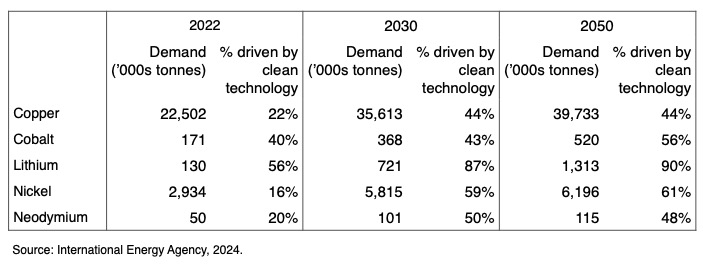

Nickel, lithium, cobalt, copper, and neodymium are among the most commonly used critical minerals in clean-energy products, which include solar PV, wind turbines, grid battery storage, electric vehicles, electricity networks, and hydrogen technologies. Significant increases in demand are expected.

Demand for selected critical minerals:

Southeast Asia holds large reserves of several key critical minerals. Measured against global reserves:

—Indonesia has 22% of nickel; 16% of tin and 4% of bauxite;

—Vietnam has roughly 18% of both rare earth elements and bauxite;

—Myanmar has about 18% of rare earth elements; and

—The Philippines has about 5% of nickel.

Cobalt reserves have also been identified in Indonesia and the Philippines.

Due to challenges in extending the value chain downstream and a lack of engagement by experienced, outside countries, Southeast Asia has begun developing domestically focused approaches. Indonesia’s approach to nickel is a strong example.

Indonesia began establishing itself as a critical mineral hub by banning exportation of raw nickel ore in 2014, allowing exceptions only for mining companies that were investing in processing. By 2020, the ban on nickel ore exports was absolute.

By requiring domestic refining, Indonesia aims at creating a value-adding industry for critical mineral resources. Formerly, it was extracting 71 million tonnes of nickel ore annually and exporting 65 million tonnes in raw form. Most went to China for smelting and use in stainless steel.

Since it imposed the ban, Indonesia has attracted significant Chinese capital investment in building local smelters, which has been led by privately owned Tsingshan Steel Group. Mine output has consequently risen ninefold. International competitors, including nickel mines in Australia, are struggling to match the capital returns and low operating costs of the Indonesian operations.

However, there are reasonable concerns about long-term environmental sustainability of upstream and downstream critical-minerals industries in Indonesia. Also, the EU has challenged the export ban in the World Trade Organization, alleging it is inconsistent with the obligation to eliminate quantitative trade restrictions.

Still, the policy has achieved its objectives. Indonesia now has a downstream nickel industry and may be tempted to ban exports of other critical minerals.

In critical minerals, China is strong in mines, processing facilities, capital, expertise and markets. Its powerful position may further complicate Southeast Asian countries’ ability to establish secure and reliable value chains. It can also use its industry strength as a coercive diplomatic tool. China alerted the world to that risk in 2010 when it used its near-monopoly in REEs to severely limit supply of them to Japan amid a territorial dispute.

Remarkably few players are in the global REE supply chain, despite the elements’ significance to sophisticated technologies. So, the United States and its allies are attempting to re-establish themselves in the field.

The Biden administration is giving the effort renewed focus, planning massive investment in climate change technology as it takes a hard-line approach to rivalry with China and the perceived national-security threat from it. Others have reacted, tool. Policy tools for diversifying supply of critical minerals include the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act, the US Inflation Reduction Act, Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategy and Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy.

Southeast Asian countries may stand to benefit from these efforts to reduce dependency on China.

And Australia may be able to help them. Its resources sector is well positioned to support development of cost-competitive Southeast Asian processing industries that meet environmental, social and governance considerations. It can offer high labour and environmental standards and technical expertise to drive production efficiencies.

This would contrast with Indonesia’s move into production of high-grade nickel through low-grade processing. Indonesia’s weaker environmental regulations may have long-term social and environmental consequences.

Southeast Asia faces a great challenge in establishing high-quality downstream industries for critical minerals while meeting environmental standards. But the challenge is not insurmountable.

Government help can reduce risks and thereby improve the prospects of projects going ahead. That help can include technical support, research and development, strategic investments to scale up processing, and locking in finance and production offtake. Meanwhile, partnerships with foreign industries can offer technology.

It won’t be easy, but Southeast Asia does have the potential to be one of the world’s major sources of critical minerals.