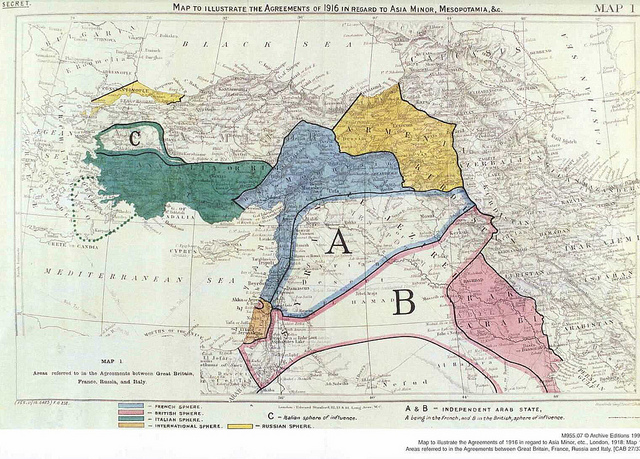

This month’s 100th anniversary of the Sykes-Picot agreement, the secret Anglo-French pact during World War I to carve French and British spheres of influence out of the then Ottoman territories of Greater Syria and Mesopotamia, has become a sort of historical I-told-you-so exercise.

The essential thesis is that a European imperial attempt to force antagonistic religious sects and ethnic groups into Europe-style nation-states was never going to work, as the crack-up of Iraq and Syria conclusively proves. Yet it’s not obvious that alternatives imaginable at the time would have been more successful.

But it’s worth examining to what extent Sykes-Picot, a perfidious stitch-up even by the squalid standards of the day, bears responsibility for failure to turn the near east lands of Greater Syria and Mesopotamia into thriving states and societies.

An often forgotten aspect of Sykes-Picot is that its intent was to constrain Anglo-French rivalry in the Levant that might have undermined the war-time alliance against Germany. Thus the region was reconfigured for the convenience of Europe’s eastern empires rather than the future cohesion of organically formed nation-states.

It’s now become almost a cliché to suggest that the break-up of Syria by the five year-old civil war, and the fracturing of Iraq after the US-led invasion of 2003, has shattered these imperially designed states into their original ethno-sectarian fragments. Even the jihadis of ISIS, after declaring their cross-border caliphate in eastern Syria and western Iraq in 2014, claimed they had “broken Sykes-Picot”.

Looking at the way the Levant has cracked into hardened fragments, divided between Sunni and Shia, Kurd or Alawite, and at how state institutions have collapsed and uncovered the hard-wiring of affiliation by sect, clan, tribe and militia, it’s hard not to see a violent reassertion of the Millet—the system of Ottoman administrative units that gave subject peoples a measure of autonomy and ethno-religious cohesion. Yet a fuller picture might look at what came before Sykes-Picot as well as what came after. The pact isn’t the sole cause of later failure—it’s maybe not even the primary cause.

To start with, the Ottoman practice of top-down autonomy based on religion built boundaries against a larger identity, restricting the idea of Ottoman citizenship to a tiny elite, in any event disabused of it by the emphatic Turkic turn in the final stages of the empire under the so-called Young Turks. That shaped the Arab future at least as much as Sykes-Picot (which in any case was not implemented as planned). So, more than arguably, did the Ottoman embrace of western military techniques but ban on the Arabic printing press, which continued (with exceptions) well into the 19th century.

The European carve-up of post-Ottoman Arab territories into heterogeneous nation-states exacerbated this legacy, and the hollow promises of pan-Arab nationalism, masking the will to power of army-based local elites, signally failed to ameliorate it. But imperial interference in the natural evolution of constitutional politics—as the British did in Egypt and Iraq and the French in Syria—probably did more to twist the future of the Arab peoples than Sykes-Picot. And that was compounded thereafter by the now US-dominated west’s fatal attraction to regional strongmen as bulwarks against communism and then Islamism, and a string of misfired interventions, from the coup against a nationalist government in Iran in 1953 to the Iraq invasion of 2003.

Little of this can be laid directly at the door of Sykes-Picot. Iran and Egypt, for example, evolved into nation-states from a state tradition established millennia before the fashion reached Europe. Nor is the case of Iraq as clear cut as it might now seem.

Part two will examine more recent developments against the backdrop of the breakup of the Ottoman territories in the Levant a century ago.