I was invited this week to be part of a panel discussion at the Australian Defence Magazine 2013 Congress. Part of the brief was to address a series of questions relating to the role of Australian Defence industry. Under the heading ‘maintaining a strong sustainment workforce in current and future market conditions’, the talking points were:

- How to avoid a skills gap

- Realigning the offshore and onshore [industry] capabilities

- Will there be a continued role for non-sovereign third party suppliers?

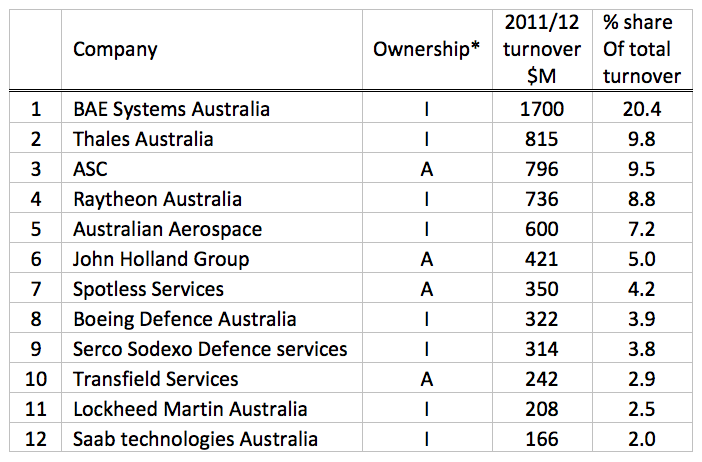

I chose to invert the order of these points, because I think that the third one informs the second and both have implications for the first—and I think the third one is based on a false premise. To see why, have a look at the top 12 Defence contractors and their turnover for the previous financial year in the table below (click to enlarge).

* I = International, A = Australian

Source: Australian Defence Magazine Dec 2012/Jan 2013

The turnover of the top 12 companies represent 80% of the 2011/12 value of the contracts being managed by Defence. Of the twelve, eight are the Australian arm of a larger international group, accounting for a 58.3% share. But of the four Australian companies, two are not providers of high-end capability products or services—John Holland Group is mostly involved in facilities works and Spotless provide maintenance services to Defence establishments around the country. That leaves only ASC—currently building the air warfare destroyers and maintaining the Collins class submarines—and Transfield Services (shipbuilding and maintenance and other services) as being involved in the delivery of capability at the ‘pointy end’.

So let’s get serious—we’re already deep into the world of non-sovereign defence capability. Those international firms are here because they provide the lion’s share of the ADF’s top-end capability. The AWDs, despite being built here, will have essentially no Australian sourced major mission systems. The fast jet air combat capability is basically a ‘turnkey’ acquisition these days. Army’s armed reconnaissance and mobility helicopters, artillery and armour are all imports. To the degree that we have a sovereign capability based on Australian sovereign industry today, it’s in the lower end of capabilities. Any real warfighting will require industrial and political support from third parties.

This isn’t an Australian unique phenomenon. The trend around the world is towards mergers of smaller companies into a shrinking number of major suppliers. This is being driven by the rising R&D and production costs that show little sign of slowing. Defence has to work within this reality and attempting to do otherwise is likely to be expensive and futile. A better question would be ‘is there a continued role for sovereign suppliers’? I would suggest that, with very few exceptions, the answer is ‘probably not’.

Consistent with that, Australian companies will increasingly have to align their skills with parent/partner companies overseas. We already have a lot of Australian companies benefitting from ‘reachback’ into companies based overseas (especially the US and UK). The good news is that the increased overall mass will make for a wider pool to draw from. The bad news is that we won’t ‘own’ many of the skill sets—but that’s increasingly the province of the very few countries still able to support the prodigious R&D costs of modern warfighting equipment.

In many ways, that should make it easier to manage any looming ‘skills gaps’. If we’re talking about the skills required to participate in a global supply chain, then the market should look after that. Either Australian companies will partner with offshore suppliers to provide a local workforce with the required expertise, or the offshore suppliers will provide an end-to-end service. Exactly how this works will depend on the relative cost of the two solutions (except when policy choices interfere with market conditions).

If, however, we’re talking about the skills required to ‘do it ourselves’, then that horse has mostly bolted. We have left a few things that have, for a variety of reasons (some good, some opportunistic and some just silly) been spared form the Darwinian process that has seen almost all our combat capability now depending on the knowhow and industrial expertise of others. One of the industries still clinging on is shipbuilding, so it’s worth a closer look at that.

I’ve written before on The Strategist about the looming skills gap in shipbuilding. (And Henry Ergas helpfully expanded on my remarks.) I’m unconvinced that it’s possible to fill that gap with anything like a sensible work program, and the odds are that we’ll still have to ramp up again, albeit from a higher base than might otherwise have been the case. The question becomes whether it’s more sensible to run down the workforce and then ramp up again, or to try to maintain a level of skill by doing projects that might not have made the cut purely on their own merits. Or, in other words, is the premium paid for building another vessel (or more) here a better business proposition than the additional costs of rebuilding skills later?

Here’s my recipe for industry or government worried about a skills gap: work out the business case. Do the sums and compare the costs and benefits of keeping a workable skill base in place versus ramping it up and down to meet intermittent demand. Like it or not, we have to be guided by the realities of the worldwide defence market and make good business decisions in that context.

Andrew Davies is a senior analyst for defence capability at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist.