When David Nicolson and his fellow soldiers in Combat Team Alpha from the Royal Australian Regiment’s 2nd Battalion served in a remote outpost in Afghanistan’s Mirabad Valley, there was a standing joke in the unit that ‘Mates don’t let mates drive Route Whale’.

The rough dirt road ran through the valley, which, in 2011, was Taliban territory and a major insurgent supply corridor. Route Whale was strewn with so many improvised bombs that it was rare for a convoy to make it home without finding one, or being hit by one.

The combat team was part of Australia’s Mentoring Task Force 3 helping train members of the Afghan National Army, which was tasked with blocking the flow of weapons and other supplies to Taliban fighters.

Nicolson recalls a stiflingly hot afternoon when the Australians were tired after a full day of patrolling on foot and climbed aboard three Bushmaster troop carriers. They passed through a small village that was normally full of people, but this time there was no one in sight. That raised anxiety levels.

Abruptly, a petrol bomb was thrown at the last of the Bushmasters and narrowly missed the gunner in his hatch at the rear of the vehicle. A massive directionally focused bomb blasted out of a wall, lifting the 15-tonne lead vehicle onto two wheels. It was poised for a time and then slammed back down.

This was the third time Nicolson had been in a vehicle hit by an improvised explosive device. ‘You black out for a second or two’, he recalled, ‘then you’re dizzy, you feel sick and sometimes you spew. Dust is everywhere. In your eyes, nose and mouth, you have that smell and taste of explosives. Your adrenaline is in overdrive.

‘While your body is going through all of this, your training kicks in and you’re making sure that you’re OK, the boys in the back are OK and casualty and damage reports are going out. You’re eyeballing the area for signs that this is a complex ambush, for signs of the enemy, the triggerman and lookouts.’

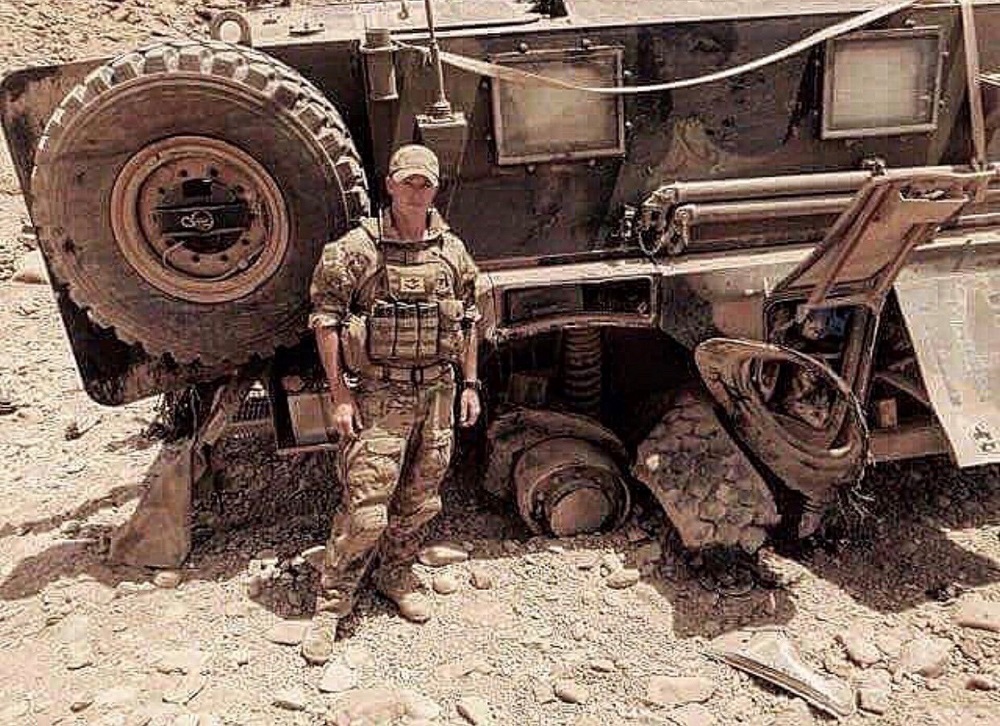

Darkness was descending as the soldiers in the stricken Bushmaster headed back to the patrol base. They moved slowly, with the front tyres shredded by shrapnel and the steering badly damaged. The bomb had demolished the external cargo bins and scarred the vehicle’s bulletproof windows, but the ‘Bushie’ was still drivable.

Before he completed his nine-month posting, Nicolson encountered a fourth bomb. He survived that, too.

David Nicolson survived four Bushmaster bombings on Route Whale in southern Afghanistan in 2011.

Nicolson emerged from Afghanistan with a great affection for the Australian-designed and -built Bushmaster. But, like many of the soldiers whose lives were saved by the nuggety vehicle, he had little appreciation of just how hard key figures had to work to bring it into production.

The policy seeds that ultimately produced the Bushmaster were planted in the Hawke government’s 1987 defence white paper, The defence of Australia, which raised the possibility of small groups of foreign troops landing in the country’s north and identified the need for ADF ground forces to be given the mobility and speed to find and deal with them. That spurred the decision to obtain a large number of lightly armoured and versatile troop carriers.

It was assessed that such raiders would arrive lightly equipped and aim to capture materials to build bombs, which were later to become ubiquitous in Iraq and Afghanistan as IEDs.

The Bushmaster’s DNA contained echoes of wars past and campaigns on continents far away. Drawing on South African and Rhodesian experiments with landmine-blast-deflecting V-shaped hulls, it was conceived as a lightly armoured truck.

Australian troops on peacekeeping missions in the Middle East and in nations such as Namibia and Cambodia saw both the devastating impact of landmines on the occupants of soft-skinned vehicles like 4WDs and the effectiveness of vehicles designed to defend against them. The peacekeepers brought home with them insights that, much later, informed the Australian defence organisation’s planning for the Bushmaster project.

It took a long time for the army to come to love ‘this massive thing’ that wasn’t intended to be a fighting vehicle and was originally sold to government as a simple off-the-shelf acquisition. Instead it became a complex development project that pushed industry and Defence into new and more productive relationships.

Even after its early operational success in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Bushmaster was to be haunted by its association in many army minds with the ‘Defence of Australia’ strategy as well as with big cuts to the service’s size, funding and role in the years after Vietnam. Some argued that anything with four wheels and no tracks was a truck and was not to be taken seriously; anyway, the tyres of this ‘armoured Winnebago’ would be chopped to pieces by rocky terrain.

Matters got so bad at one point that, in December 2001, the team charged with overseeing such programs, the Defence Capability and Investment Committee, wrote to Defence Minister Robert Hill recommending that the project be abandoned.

Hill shared the committee’s concerns about the project running late and well over budget but says he was persuaded by the Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Peter Cosgrove, to keep it going because troops in future wars would need a high level of protection.

Ultimately, the Bushmaster faced a reality very different from what was envisaged—not a conflict fought on the red soil of northern Australia but a series of brutal battles and running fights in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Events created a desperate need for such a vehicle. Tragedies in Iraq and Afghanistan showed the vulnerability of troops, even the most capable special forces, when operating soft-skinned vehicles against insurgents with the technical know-how to build IEDs and the tactical skill to employ them well.

There was nothing else readily available on the world market. US troops in Iraq were welding additional steel plates onto their own poorly protected vehicles.

The Bushmaster’s capability wasn’t fully appreciated until it was in action and by then it was seen to be a defining reason why so many Australian soldiers survived IED blasts while British and American lives were lost.

After bombings in Afghanistan, troops sent back technical reports and ‘tiger teams’ of engineers and scientists were sent to the war zone to examine the damage and to find ways to strengthen the vehicle. The manufacturer, Thales, was able to improve Bushmasters on the production line and in the operational area.

A cheaper, off-the-shelf vehicle from overseas would not have given Australia the flexibility to adapt to changing enemy tactics in Afghanistan. Indeed, the way industry, the army, Defence scientists and others worked so quickly and effectively together to harden the Bushmaster against ever more devastating IEDs is a model of the ‘fundamental input to capability’ idea that promotes innovative work between Defence and industry.

Ultimately, the Bushmaster proved itself a lifesaver in combat and vindicated those who had faith in it.