It’s been nearly two months since China’s official media agency Xinhua debuted #Xiplomacy on Twitter. Xinhua, with a weighty 11 million Twitter followers, initially used the hashtag to push out a new multipart documentary series on President Xi Jinping’s diplomacy (you can stream episodes 1–6 on Xinhua’s YouTube account here).

But hashtag harmony didn’t last long; by mid-September it had been co-opted, filled with tweets and memes by netizens who don’t share the #Xiplomacy vision. With Twitter banned in China—and on a social media network with an immediate and largely uncensored feedback loop—it was always going to be difficult for Xinhua to prop up the hashtag and keep it trucking in its intended direction.

Social media platforms now play an incredibly important role in how states—both overtly and covertly—engage and attempt to influence populations overseas. China has never ranked highly in the world of digital diplomacy but that’s quickly changing.

Over the past two years, the Chinese government has upped the ante with a global multimedia strategy that leverages China’s state-owned media outfits. The strategy is particularly heavy on animation, music and storytelling (and sometimes all three!)

Xinhua has developed a set of videos laying out China’s vision and point of view—on topics such as China’s South China Sea claims, its military power, the One Belt, One Road initiative and the recent 19th National Party Congress. And those videos will be promoted across the world via different platforms and multiple video-streaming sites. It’s a clever way to tell, re-tell and argue for a strategic and global narrative. And it certainly helps that many of them are fun and easy to digest.

Last month the New York Times revealed that Facebook had helped state broadcaster CCTV set up a Facebook page for President Xi Jinping. A small but very interesting detail to emerge as Facebook continues its efforts to crack the Chinese market. Called ‘Xi’s Visit’, the Facebook page provides almost daily updates on the president’s schedule, with a particular focus on his overseas trips and his attendance at multilateral events in China. It, too, turns to animated videos to explain China’s foreign policies.

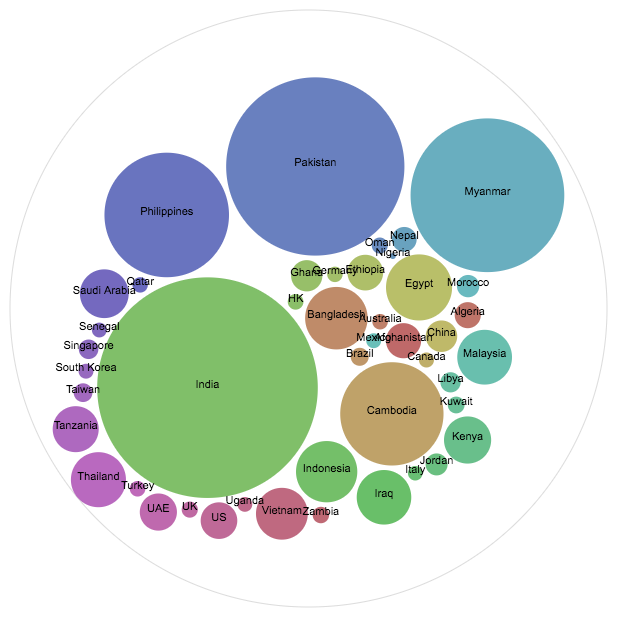

The geography of President Xi Jinping’s followers also paints a particularly interesting picture. So who’s listening?

Geography of likes for ‘Xi’s Visit’ Facebook page. Graphic created by Danielle Cave, September 2017

Not Australians. And few living in western democracies. But neighbours to China’s south are, despite often low internet penetration rates, which put a third, or less, of their populations online. Xi’s friend count is highest in India (733,900), followed by Pakistan (480,000), Myanmar (356,000), the Philippines (240,000), Cambodia (161,000) and Indonesia (56,600). Not bad figures for a two-year-old Facebook account that appears to put minimal effort into recruiting new friends.

Online influence isn’t only about reach and, as Russia’s bold and sophisticated cyber interference has highlighted, it’s not only overt. Government social media accounts tend to amplify events and third-party content and they struggle with genuine engagement and influence. Building a narrative that explains who you are, what you want the world to look like and how you intend to get there is hard. Proactively and strategically communicating that narrative online in a way that’s targeted, convincing and effectual is even harder.

The Chinese government’s intensified efforts to get its narrative out there—even if not everyone is buying what it’s selling—are impressive. These efforts provide a lot of lessons for Australia as we wait for the government to release a new foreign policy white paper. While we’re unlikely to turn to rap videos to promote our foreign and defence policies, we do need to ask and answer an important set of questions, starting with: What’s Australia’s strategic narrative? Who’s listening? And how can we better cut through?