A couple of weeks ago my colleague Toby Feakin, wrote on The Strategist about the recently released United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s assessment on Transnational Organized Crime in East Asia and the Pacific, pointing out how international crime is a dynamic and complex phenomenon that ‘remains a threat to security and prosperity across the region’.

Toby highlighted how the groups that perpetrate these criminal acts

… have benefited from the globalisation process, and the technologies it provides, to operate across borders, creating new linkages between groups to maximise financial profit, while minimising the risks of being caught. They’re often formed like agile businesses, have no desire to become involved in the use of physical force just for the sake of it, and are highly adept at reshaping themselves to fit the illicit economies that they’re servicing. The groups are highly mobile, flexible and operate in multiple jurisdictions and criminal sectors, exploiting legislative loopholes where they exist, and are aided by the illicit use of the internet.

The UNODC report sends a clear message that transnational crime isn’t a homogeneous phenomenon, but rather a very diverse set of activities. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach won’t work: each aspect will need carefully crafted policy and operational responses.

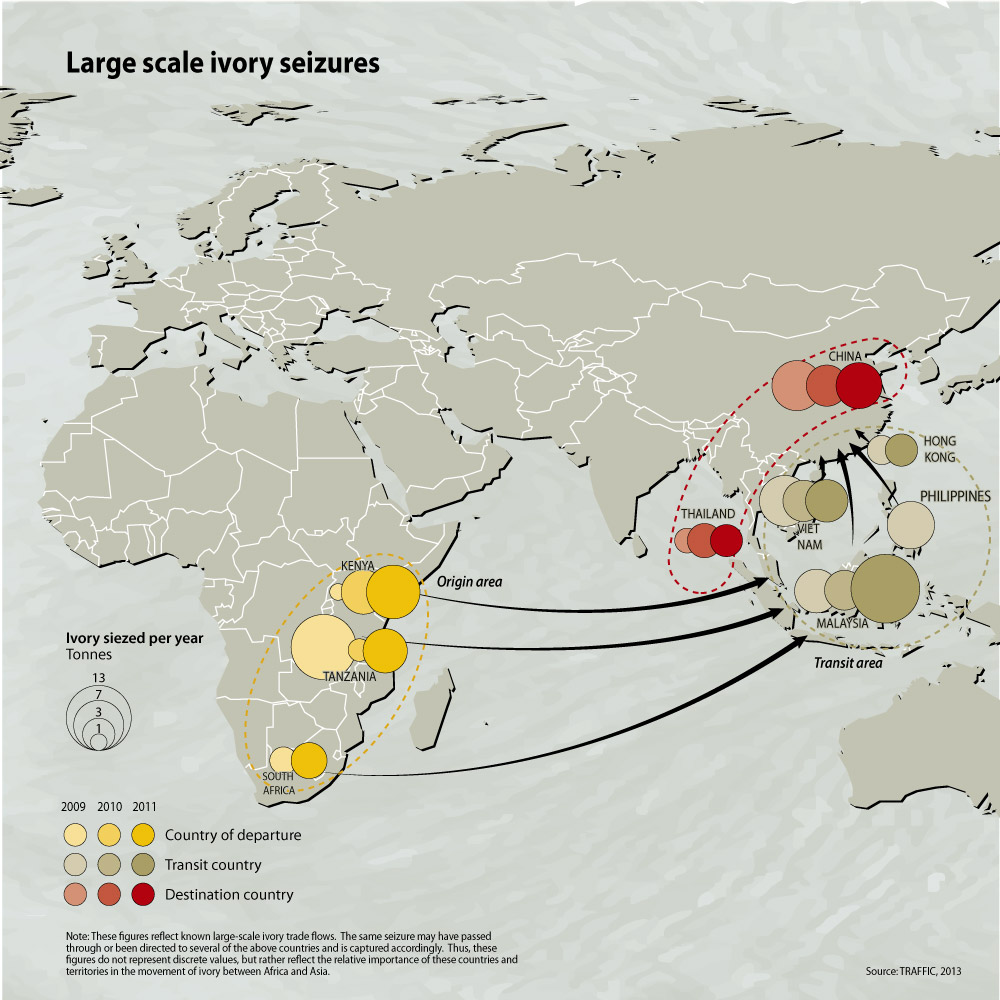

To give one example, there’s now a growing and extensively documented (large PDF) link between conservation, development, crime and security in the illegal ivory trade. That trade is mostly driven by the so-called ‘gang of eight’: exporters Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda; middleman states Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines; and consumers in China and Thailand.

Most ivory is obtained illegally from Africa and manufactured and sold in Asia. Elephants from east and southern Africa are stripped of their ivory, which is shipped to Southeast Asia to be turned into commercial products, and then often on shipped to Thailand and China.

The Ministers of the Economic Community of Central African States recently called on ivory consuming countries to take drastic measures to deter consumers and urged the poachers’ countries of origin to support affected countries in combating poaching. They’ve agreed to mobilise joint military operations to protect savannah elephants.

There’s a growing consensus around the need to act. Last September at the UN General Assembly, heads of state discussed the dangers to stability and rule of law from the illegal trade of natural resources. Former Secretary of State Hilary Clinton argued last year that wildlife trafficking needs to be addressed decisively. Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in March highlighted the importance of coordinating enforcement support at global, regional and national levels, deploying a wider-range of operational techniques and reducing demand for illicit goods.

As I’ve argued recently (PDF), with reference to the trade in ‘blood ivory’, Australia needs to work with China, and regional transit states to share intelligence with regional customs agencies on the illegal wildlife trade. One way to do this would be for AusAID to focus on wildlife conservation in its African strategy, and we should be taking up the issue with the African Union. Our presidency of the UN Security Council in September also provides an opportunity to raise the security aspects of transnational wildlife crime.

Issues related to poverty eradication, security and governance in Africa will feature at the inaugural Aus-Africa Dialogue this year, sponsored by ASPI and South Africa’s Brenthurst Foundation. The Dialogue will no doubt raise the question of transnational wildlife crime. While this is a conservation issue, it’s not solely an issue for conservationists.

Anthony Bergin is deputy director of ASPI. Image courtesy of GRIDA.