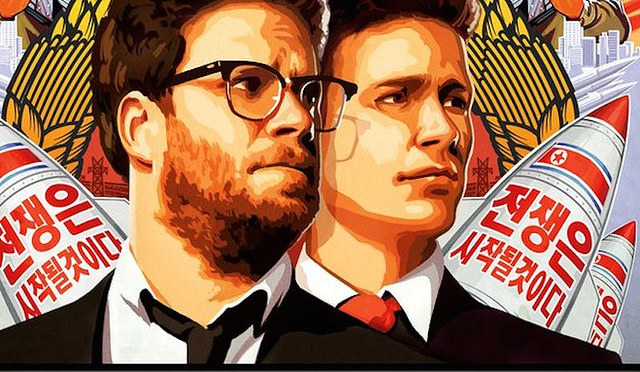

Late last week, the US Department of Justice filed a criminal complaint against a North Korean hacker—who allegedly acted on behalf of the North Korean government—in connection with a series of cyberattacks, including the cyber intrusion and attack against Sony Pictures in 2014. Among other things, this individual, along with other unidentified hackers, is alleged to be part of the Lazarus Group, which has been implicated in a wide range of malicious cyber activities—including the destructive WannaCry 2.0 worm that affected computers around the world in 2017 and the attempt to steal hundreds of millions from the Bangladesh Bank in 2016.

This is the first time that the US has criminally charged a North Korean government hacker and, like the indictment of five PLA officers for intellectual property theft a few years ago, it’s extremely unlikely that the charged individual (who apparently is in North Korea) will ever see the inside of a US courtroom. The charges are also unlikely to have any real effect on the malign cyber behaviour of North Korea. Unless other measures are brought to bear, North Korea isn’t really susceptible to being ‘shamed’, even when called out in such detail.

Nevertheless, the criminal complaint and supporting affidavit serve an important purpose. They demonstrate that, although it may take time, the US will expose malicious nation-state activity, including the individuals responsible and their tradecraft, for the world to see. Though more is required to achieve effective deterrence, this development sends an important foundational message, particularly when many doubt that effective attribution is possible.

I was part of the US government when we were dealing with the Sony attack in 2014. In one of the first instances of US government attribution of cyber conduct to a nation-state, President Barack Obama called a news conference and announced that North Korea was responsible. Shortly thereafter, he imposed sanctions on North Korea because of that and other activity. It was a watershed moment— to make public attribution at the highest level of our government sent a strong message that malicious state cyber activity would not be tolerated.

The move was coupled with extensive diplomatic outreach to allies and partners around the world to share our views and build support. Indeed that, and our outreach to partners in response to the Iranian distributed denial-of-service attacks against many of our financial institutions, served as the basis for our work to build a collective response by countries against shared cyber threats that continues today.

Still, the experience was also somewhat frustrating. Although nearly every commentator and researcher had said that North Korea was behind the Sony attack before Obama’s landmark press conference, many voiced doubts once the president and the US government went on the record. They challenged the evidence we put forth publicly as incomplete and instead offered a variety of alternative, often conspiratorial, theories.

The US government released far more corroborating information than it normally would, particularly when, as was the case then, no public criminal charges were brought. But it’s unreasonable to expect the US, or any government, to release all the information it has that led to attribution, especially when that information is particularly sensitive or could compromise sources and methods that are important in tracking and preventing future activity. This practice is no different from how attribution is handled for physical-world incidents. At the end of the day, in cyberspace or the physical world, attribution is a political (small p) decision based on all the information available. Countries nevertheless want to be highly confident that they’re right, because being wrong undermines future credibility and action.

Russian government representatives also tried to cast doubt on the attribution of North Korea, making the self-serving claim (especially in light of all the malicious cyber and physical activity they’re responsible for) that if one country is going to accuse another, the attribution must be essentially 100% ironclad based on publicly released evidence.

The Russian position fits in with Moscow’s practice of denying its involvement in everything from election interference to NotPetya in the cyber world, and from the UK poisonings to the Ukraine incursions in the physical one. Even when I was a federal prosecutor, the standard of proof when an individual’s liberty was at stake was never absolute but was instead beyond a reasonable doubt. Demanding absolute proof is a convenient way to deny malicious actions even when it’s clear who the perpetrator is. It’s also used as a subterfuge for getting insights into the information held by other countries to evade detection in the future.

The complaint and 179-page supporting affidavit in this case should help lay to rest a lot of the groundless claims that there wasn’t a strong factual basis for accusing North Korea. The affidavit is remarkable in its thoroughness and detail. I agree with those who have said that it reads like a thorough threat intelligence report with a criminal charging overlay. My former Justice and law enforcement colleagues deserve a lot of credit for all the work that went into the investigation. In any event, it tells a compelling story of the scope and scale of North Korean cyber activity. The fact that it fingers individuals (one by name) and organisations, and that it lays bare at least some of North Korea’s tradecraft in detail, alone make the document important.

The targeted sanctions imposed concurrently on the defendant and on a Chinese firm that employed him are also helpful. Though China and the US differ on many things, and we rightly remain concerned about Chinese malicious cyber activity, I think there’s some opportunity for common ground with China, assuming that it wouldn’t want rogue actors from other countries operating from its soil and, potentially, causing instability or exposing it to blame.

The criminal complaint and sanctions, though good, are still unlikely to deter North Korean actions in the future. For that to happen, they need to be part of a comprehensive plan that, among other things, includes putting pressure on the North Korean regime. Like with Russia, or any state adversary, that will require consistent, high-level messaging from the top. Sadly, that is lacking.

I’ve written before that, regardless the activities the US takes to hold Russia accountable for its malicious cyber activity, those efforts are undermined when the president himself not only refuses to publicly endorse them but undercuts those actions by casting doubt on Russia’s involvement. With North Korea, I fully understood why cyber issues wouldn’t be prominently raised during the first US–North Korea summit given the importance of denuclearisation, but thought it needed to be embedded in future dialogue with North Korea. Of course, the talks with North Korea seem largely on the rocks, but whatever their fate, it doesn’t seem likely that cyber matters will be raised despite last week’s charges. Worse yet, on the very morning that the criminal charges were announced, President Donald Trump tweeted about how well he and Kim Jong-un get along — hardly the messaging, on at least this topic, that’s likely to provoke North Korea to stop its activity.

Until we can do a better and more comprehensive job of pushing back on North Korea’s and other nation-states’ cyber activities, the use of criminal charges and other tools can only help lay an important foundation. But they will not, without more, deter our adversaries.