I admire the sophistication and drive of the Chinese state in manoeuvring within Australia’s federal system of government to secure official sign-up to President Xi Jinping’s signature geostrategic and economic initiative—the Belt and Road Initiative.

Chinese officials have understood the different dynamics, perspectives, knowledge and motivation at state-level administration in Australia well, and perhaps even exploited the particularly vibrant election period in Victoria.

I am stunned that this sophistication and drive haven’t been understood—or, better yet, matched—by Australian statecraft and federal–state government cooperation. We have been outmanoeuvred, outplayed and made to look at least partly naive and perhaps partly just plain greedy.

The Australian government has been wary of signing up to the BRI without clarity from Beijing about two big things: what the Chinese state’s motives are in advancing the BRI, and how the multitude of individual projects are planned, decided on, funded and implemented.

That wariness has been vindicated by recent troubles with iconic BRI programs.

In fact, there’s a strong debate within China about whether the BRI needs to be recast to address rising international pushback because of its lack of transparency, the financial burdens it puts on recipients and its seemingly strong political and security implications.

We’ve seen the new Malaysian prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, travel to Beijing and announce clearly and politely that he was cancelling some US$22 billion in BRI projects with Chinese firms and banks because of corruption in these deals and the lack of value for money to Malaysian taxpayers.

Tonga’s prime minister, Akilisi Pohiva, has publicly asked Beijing to forgive the US$160 million that Tonga owes Chinese construction firms for rebuilding much of the island’s commercial centre, because it couldn’t make the repayments.

The International Monetary Fund has been calling for details of Pakistan’s US$60 billion in BRI deals and debt that make up the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor package, because without them it can’t understand Pakistan’s financial position and so can’t define an assistance package to help the country through its emerging financial crisis.

And finally, for those who doubted that the BRI was more than just a big package of economic investments in infrastructure for various noble purposes, we have Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port. The Sri Lankan government was told that the port would be a commercial success and bring much-needed economic activity to Sri Lanka.

It wasn’t and it didn’t. The Sri Lankan government was unable to make the repayments on the Chinese loans that financed the project. As a solution, China took a 99-year lease on the port and now operates it, opening up all kinds of opportunities for reuse—perhaps including an expanded Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean.

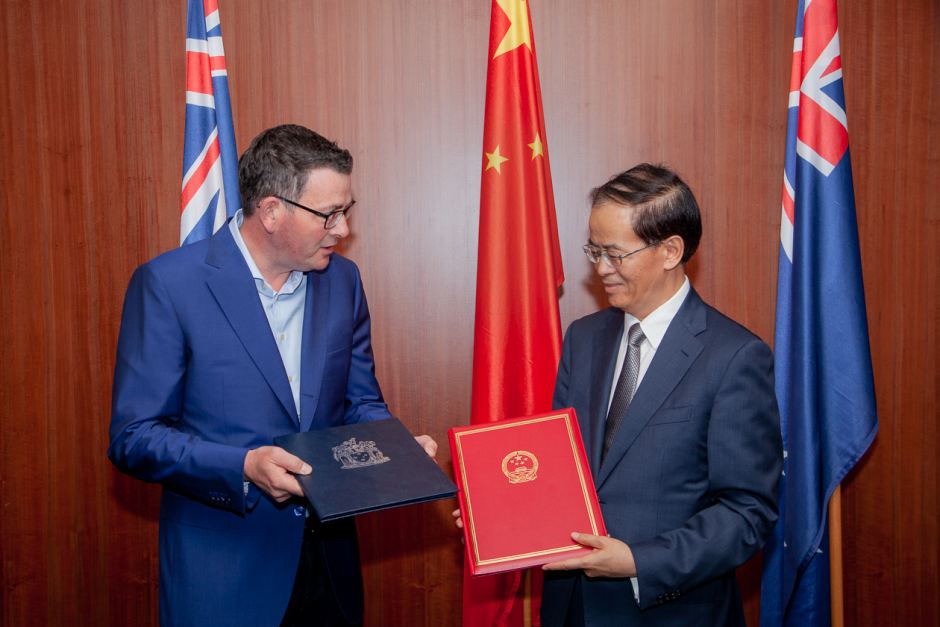

Now to Victoria.

How does it come to pass that a state government has signed up to not just any old commitment with a foreign government, but to the BRI—despite the fact that, for foreign policy and security reasons, the Australian government had already actively decided not to sign up to an overarching BRI deal?

How is it that the Australian trade minister can say he supports Victoria’s decision, while admitting that he hasn’t seen the contents of the memorandum of understanding signed by Victoria and China?

The federal government hasn’t actually welcomed the Victorian move, although it has kept its criticism low key. Both Simon Birmingham and Foreign Minister Marise Payne have quietly noted that, rather than signing up to the BRI as a whole, Australian policy has been to engage with specific projects that ‘are sustainable [and] provide clear benefits for the recipients’.

That’s code for concern about Beijing’s overall lack of transparency and the underlying intent of BRI activities. But at a time when Birmingham is in China and Payne is going there this week, no doubt they want to keep things calm and quiet.

So how did it happen? I think much of the explanation comes from misunderstanding and opportunism.

From the Victorian government’s perspective, it probably seemed a great idea to get ‘first mover’ advantages by getting in early on the BRI, perhaps with some notions that being the first Australian government—federal or state—to sign up would have rewards.

Maybe it was simply viewed from an economic benefit perspective and strategic, geopolitical or foreign policy factors just didn’t come into it—because such things aren’t part of state government responsibilities in our federal system.

You can hear that in how the China Daily reported Victoria’s move:

Wang Yiwei, director of the Renmin University of China’s Institute of International Affairs, told the Global Times on Sunday that Victoria is a state that is more focused on business than politics compared to Australia’s capital Canberra.

While Canberra deals more with issues related to national security and ideology, local governments tend to be more practical in their cooperation, Wang said.

Sadly, he seems spot on … if ‘practical’ is meant as a synonym for naive.

If the Victorian government had received intelligence briefings from national security agencies on Chinese investment and foreign interference and influence, it’s hard to imagine them not understanding that the BRI has both a strategic and economic agenda. Or that the BRI plays a huge role in Xi’s drive to create a China-centred region that supports the assertive power ambitions and perpetual rule of the Chinese Communist Party.

If they have been following the growing criticism of and controversy over the BRI, it’s hard to see how they can think that signing up now is a smart move.

If they had understood that any level of Australian government signing up would be used by the Chinese authorities as a brand endorsement that helps address the growing criticism, maybe they would have had second thoughts.

One contributor to the Victorian government’s decision might be advice from the Australia–China Belt and Road Initiative, a Melbourne-based lobby group set up to ‘help Australian business gain clarity on Belt and Road opportunities’. Such advocacy aligns neatly with Beijing’s narrative on the BRI and ignores the broader implications for Australia’s national interest.

Despite being under pressure to reveal what is in the MoU, the Victorian government has refused to release details. It’s not clear whether that’s because the MoU is a shell agreement or because it contains text that the Australian public may not appreciate.

I wonder if ACBRI or other external lobbyists and advisers to the Victorian government know what’s in the document.

But it’s ironic that Victoria has added to the opacity surrounding the BRI rather than supporting the greater transparency that Australian and other leaders like Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe are calling for from Beijing.

If Beijing wanted to see whether there was a coherent federal- and state-level approach to the most important strategic and economic issue of our time—Australia’s China policy—this experience would have helped Chinese decision-makers relax.

It tells Beijing that there’s plenty of room to manouevre within the contradictions of the fractured Australian political system. Both Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Opposition Leader Bill Shorten have started to address this, but there is much to do.

What we have here is another fantastic example of the need for a clear, publicly stated policy that actively balances the large economic opportunities China offers and the significant and growing areas of strategic difference between the Chinese state and Australia.

Having such a policy at the federal level would assist all tiers of government and help business and the Australian public deal with the actions of an assertive, authoritarian, repressive, powerful one-party state with which we have close economic relations.

What’s needed is a policy on China for Australia as a nation, not just as an economy.