Cybercrime is presenting law enforcement agencies worldwide with new and evolving legislative problems and operational challenges. Identifying and stopping nefarious online actors, many of whom are based thousands of kilometres away on foreign soil, is a challenging, endless and often thankless task. But this is now being complicated by a trend towards increasing vigilantism on the cyber frontier.

Frustrated by relentless and increasingly sophisticated infiltration attempts, businesses and corporate heavyweights are discussing with increasing vigour how to return fire.

Defence is a comparatively weak strategy in cyberspace—it’s only a matter of when, not if, most networks will be infiltrated. Savvy firms aware of this reality are employing several pre-emptive tactics such as planting misleading information on their own servers or creating endless rabbit holes to lure in intruders and keep them occupied.

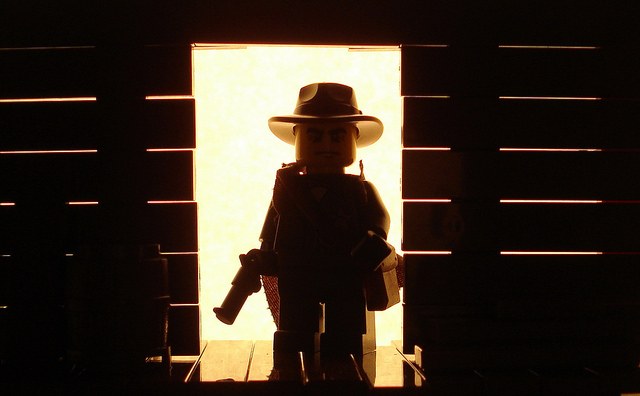

Dubbed by some as ‘active cyber defence’, that approach works to raise the overall cyber resilience of companies. It’s a lawful and proactive way to guard against cybercrime—the equivalent of strengthening the bank vault in a Wild West town. But it must remain confined to company networks.

Some businesses are moving off their own servers and pursuing more aggressive, retaliatory tactics against cybercriminals. That is, they’re not just hardening and hiding the vault, but actively pursuing bank-robbers. And that’s creating problems for law enforcement and governments.

Some corporations are unhappy with strategies restricted to their own networks, deriding it as ‘passive cyber defence’. Former US Ambassador to China, Jon Huntsman, is the latest to lend his voice to the chorus, calling for more freedom to pursue stolen information through cyberspace. In June, campaigners were even advocating for the broad application of the Second Amendment to the online environment.

While ’hacking-back’ and directly attacking cybercriminals may seem just and gratifying, that strategy is illegal in most countries and counter to the norm of a stable and crime-free cyberspace that’s being pushed so vehemently by Western countries.

Many of the computers used to penetrate company networks are often legitimate private computers that have been hijacked by criminal organisations to route their attacks through. Illegal botnets comprised of ensnared private computers can be similarly used to automatically probe for network weaknesses.

Counter-attacks against those computers are extremely unlikely to help regain stolen corporate information or intellectual property and can adversely impact an innocent third party.

If those third-party systems turn out to be controlling critical national infrastructures or belong to major corporations, the knock-on effects and implications of any damage to those networks could be calamitous.

In short, any form of offensive attack, against innocent users or otherwise, has the potential to land IT departments and contractors in hot water. Any unauthorised movement into the private network of another holds significant legal implications in some countries, in particular the United States, where the intent of the user in hacking cases is irrelevant.

When speaking to an American Bar Association panel about hacking back, a representative of the US Justice Department explained that the first reaction of his team was ’Oh wow – now I have two crimes.’

In Australia, the legislative waters surrounding hacking back are murkier. But as a signatory to the Budapest Convention Australia is obligated to work with foreign governments to pursue hackers within our jurisdiction and potentially extradite them, as the treaty outlaws private retaliation.

We’re yet to see the extradition of anyone under the convention, but it’ll be interesting to see how the Australian Government would handle such a request from a foreign government, particularly if crime wasn’t the primary motivation of the hacker.

Improving cyber resilience should continue to be a high-level goal for businesses world-wide. But countering cybercrime shouldn’t come at the cost of the safety of ‘innocent’ third parties. Disruptive techniques within the realms of one’s own server are acceptable, but it’s when vigilantism spreads that fight to the servers of others that the Western norm of a stable cyberspace is threatened.

Jessica Woodall is an analyst in ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre. Image courtesy of Alex Eylar.