On Saturday, former Chinese Communist Party general secretary Hu Jintao was dramatically removed from the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, as the 20th party congress came to a close. Footage of the closing ceremony, recorded for the world’s media to see, showed two men escorting Hu from his seat as General Secretary Xi Jinping, directly next to him, looked on and offered no assistance.

State media outlet Xinhua claimed that Hu was escorted out because he ‘was not feeling well’. That might be true. But the scenes also might have depicted something more sinister. Hu appeared confused as he was pulled away and tried to sit back down. Other top party leaders appeared surprised too. Previous National People’s Congress chairman Li Zhanshu (a Xi ally who on Saturday, as expected, was left off the CCP Central Committee, a group of 205 top party officials, and is no longer on the Politburo Standing Committee) appeared to try to assist Hu.

But, Wang Huning, a top adviser and ally of Xi, then seemed to tug Li back. Maybe he was encouraging Li not to become involved; maybe he knew something that Li did not. We don’t know. So, analysts should consider all possibilities, including that Xi deliberately orchestrated the incident to publicly humiliate his visibly ageing predecessor.

The CCP, after all, is a brutal organisation. Surviving its politics and accumulating power within it require a person to be particularly cunning; otherwise, their chances of survival are low. And, importantly, a rise to power is never a guarantee of power.

Hu is a member of the network of political alliances known as the Tuanpai (团派), or the (Communist) ‘Youth League Faction’. It consists of members of the party who rose to power with Hu Yaobang as their backer. Xi is China’s first leader from the Red Guard generation. The Youth League faction is a group Xi has continually marginalised as he has sought to solidify his grip on power.

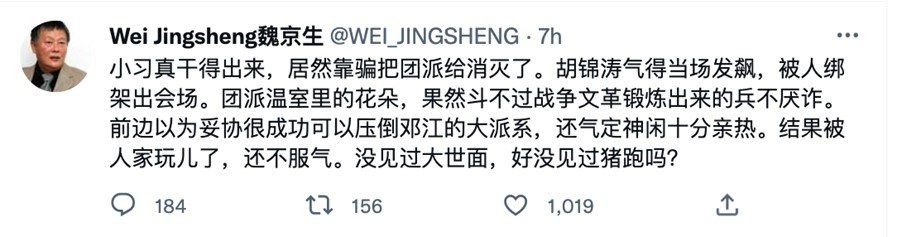

Wei Jingsheng is a US-based human rights activist and former political prisoner in China (from 1979 to 1997, under Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin; he was only briefly released for a few months in 1993). Wei was imprisoned for calling for democratic reform, after realising that the party inflicted famine on its own people, though prior to that he was himself a Red Guard. He personally knows more about power in the CCP than most Western commentators. He reacted on Twitter:

Little Xi really did it, and has unexpectedly put an end to the Youth League Faction by deceit. Hu Jintao lost his temper on the spot, and was kidnapped from the meeting [as a result]. The Youth League Faction are flowers that grew in greenhouses, and there is no way they could win in a struggle against those who were trained in an actual fight that is the Cultural Revolution, where [they learned] that soldiers should never be tired of deceit and cunning in war. Initially, Hu thought a compromise would help the Youth League suppress the Deng/Jiang factions so they leisurely cosied up to the Xi camp. As a result, they were played by Xi, and still seem rather undignified. What? What? They’ve never seen how the world really works, or how a pig is supposed to run [from the Chinese slang term meaning that even if you’re too poor to have pork, you’ve at least seen a pig running somewhere]?

Wei is referring to the fact that Premier Li Keqiang and Vice-Premier Wang Yang were surprisingly left off the CCP Central Committee. It’s a pretty big deal. Li was expected to step down as premier but could have stayed on the standing committee, and Wang was tipped by many to be promoted to premier. Both Li and Wang are also members of the Youth League Faction.

Wei suggests that Xi deceived Hu, and in the moments before didn’t follow through with a political deal Hu thought had been struck, so Hu reacted angrily and was escorted out.

What’s next for Hu is unknown. If he really was just ill, then perhaps we’ll see him in the future, sitting in the front row as expected. But if Hu’s removal plays out to be a theatrical display of Xi’s political power, then perhaps we’ll learn at some point that Hu has been purged. Or maybe it will stop at what we saw on Saturday night, and we’ll never know for sure. In any case, it’s important to remember that political opponents of the CCP often ‘fall ill’ or die in very questionable circumstances. The political environment does nothing to stop the rumour mill.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that Hu has been blamed within the party for enabling a weak environment that allowed corruption to thrive. Xi claims to be dealing with that through his anti-corruption campaign, though corruption accusations are about politics and personal power over and above stamping out graft. Xi’s campaign has come very close to Hu. His former close aide Ling Jihua was sentenced to life in prison in 2016 for corruption.

Xi’s report at the beginning of the party congress was highly critical of Hu’s leadership, though with the corruption campaign that has been a persistent theme under Xi. Still, the language in the work report seems particularly condemning and direct, and blames a situation that was inherited, specifically in the section outlining the situation when Xi took office a decade ago. Here, the report says: ‘Some party members and officials were wavering in their political conviction. Despite repeated warnings, pointless formalities, bureaucratism, hedonism and extravagance persisted in some localities and departments. Privilege-seeking mindsets and practices posed a serious problem, and some deeply shocking cases of corruption had been uncovered.’ Xi’s 2017 report at the 19th party congress used some similar language, but those comments were contextualised more around what he had done to confront the issues in the previous five years.

Through his leadership and political decisions, including the corruption campaign, Xi has generated a lot of discontent among elite families of the CCP. It’s an area in which even recently it has appeared that he hasn’t fully neutralised opposition. In September, just before the congress, there were rumours of a coup attempt against Xi. He appeared publicly soon after, but the idea that his grip on power might have been more precarious than had been assumed was still worth taking seriously.

Under these circumstances, Xi could have used Hu to send a chilling statement to any opponents. We know that Xi has effectively silenced a lot of opposition, but his actions show that he still perceives threat. If Hu’s removal was political and not health related, it may lend more credence to this idea. Such a public display could be interpreted as a forceful assertion of blunt power against those in the party who oppose Xi. After all, the greatest crises acutely threatening the CCP’s power have come from inside the party itself. And, as Xi must know personally, the threat isn’t usually imagined.

In fact, this wasn’t the first time we’d heard about an alleged attempt to disrupt Xi’s power. Zhou Yongkang was responsible for the massive expansion of the electronic surveillance that has continued under Xi. Even though those Hu-era efforts persist, Zhou and his allies were among the ‘tigers’ taken down in Xi’s anti-corruption campaign. A 2016 book accused Zhou and other tigers of being orchestrators of ‘political plot activities’ aimed at ‘wrecking and splitting the party’. A similar December 2016 Seeking Truth article accused them of having ‘inflated political ambition’, which led to political conspiracy and ‘undermined the party’s organisation’ and unity. Something happened, even though we may never know exactly what.

Even amid the tight security of the party congress, there have been reports that people in China have been receiving iPhone AirDrop messages denouncing Xi. It’s hard to say what the source of those might be, but whether or not something like this is organised from outside or inside China, opposition is real. A few small protests were also reported, successful incidents for their organisers in a time of massively increased public security measures designed to prevent such demonstrations from taking place at all.

The scariest thing is that if Xi perceives an acute threat to his power, it might be from this that he draws the most strength. And this might be the underlying explanation for Hu’s ejection, even if the logic doesn’t quite compute for analysts of China who realise just how unusual the publicness of the incident feels in recent party history.

Xi’s new Politburo Standing Committee is more packed with loyalists than before. They collectively don’t have the bureaucratic experience of previous members. But, for Xi, loyalty is more important than any relevant experience. With added confidence coupled with any perception of threat, Xi might just be bold enough to take other shocking actions in the political domain. On these grounds it’s fair to say Xi’s corruption campaign will probably continue strongly, and possibly become even more brazen in his third term, with or without Hu being purged.

This confidence and perception of threat, which was also clear in Xi’s party congress report, doesn’t bode well for the world’s security. A person drunk on power often makes catastrophic decisions. When that person is in charge of a country that isn’t afraid to be openly adversarial with the rest of the world, these events may portend a dangerous moment. Xi is a person who clearly will do whatever it takes to expand his power, and he has shown no caution in exhibiting this character both inside and outside of China’s borders.