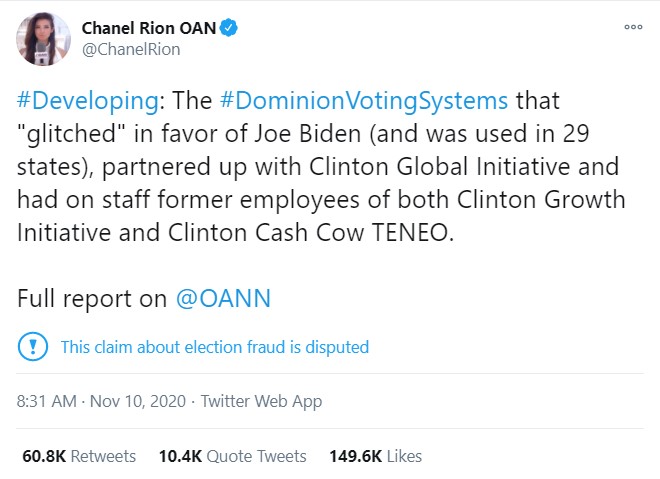

On 10 November, a journalist with the right-wing news network One America News (OAN) tweeted the unsubstantiated claim that voting technology used in Michigan and Georgia had ‘glitched’ for Joe Biden. Her tweet was retweeted by President Donald Trump.

The post was dutifully marked by Twitter as a ‘disputed’ claim about election fraud. But on YouTube and Facebook, OAN’s claim didn’t receive the same treatment.

Dominion Voting Systems, whose equipment was used in several states, had some technical difficulties on election day. But the suggestion that the technology switched votes to the president-elect has been debunked multiple times.

Yet this falsehood is one of many seeking to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the election in the hyperactive and interconnected ecosystem of cable news, conservative news websites and social media. Conspiracies about dead voters now flow quickly from politicians on Fox News to YouTube. Rumours about switched votes spread from web forums to right-wing blogs to YouTube, and to the president’s own Twitter account.

But despite the quick way such ideas metastasise, social media platforms seem to have largely been moderated during the election as separate islands, with their own domestic rules and norms. Twitter, for example, added a warning label to the OAN reporter’s tweet as part of its policy to add context to disputed claims about the election. At last check, the post had been retweeted more than 71,000 times. Twitter moderators also added the label to an OAN tweet that contained a link to her report on YouTube.

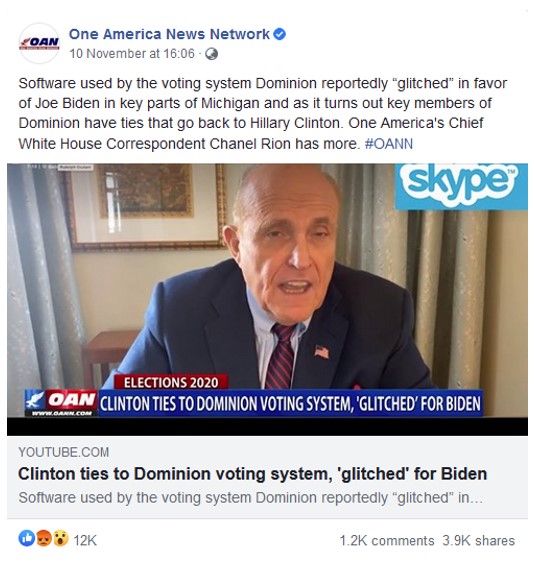

But on YouTube itself, where the approach to election misinformation has been called ‘light touch’, OAN’s video about the claim appeared without any warning notice and was viewed almost 204,000 times. While YouTube says it removes videos that ‘mislead people about voting’—such as those publicising the wrong voting date—views on the outcome of the election are allowed.

The YouTube video travelled further still. It was shared on OAN’s Facebook page, where it received more than 18,000 interactions in the form of reactions, comments and shares, according to the insight tool CrowdTangle.

Before the election, Facebook said it would attach ‘an informational label’ to content that discussed issues of legitimacy of the election, but one did not appear on OAN’s YouTube clip on Facebook. Overall, the YouTube link received more than 40,000 interactions on Facebook. Just under half of those took place on public pages, suggesting it was also shared widely in private Facebook groups, which are difficult for researchers to access.

This inconsistency, while not surprising, is increasingly problematic. The spread of disinformation aimed at discrediting the results of the US election has again underscored that a disjointed approach is ineffective at mitigating the problem, with potentially disastrous consequences for democratic institutions. In an environment where a video removed from YouTube spreads on Facebook—not to mention TikTok, Parler or dozens of other platforms—some may demand a uniform approach.

The platforms do collaborate on some law enforcement and national security issues. For example, all three companies are part of initiatives to share hashes—unique fingerprints for images and video—to stop the spread of violent imagery and child exploitation material.

But coordinated efforts on disinformation have largely focused on removing foreign and state-backed disinformation campaigns. Domestic misinformation and disinformation, which became the main challenge during the US election, rarely evokes similarly unified efforts from the big three, at least publicly.

Pressure is intensifying for the platforms to ‘do something’. Yet forcing all of the major companies to work together and take the same approach could result in what Evelyn Douek, a lecturer at Harvard Law School, has called ‘content cartels’.

Decisions about what stays online and what gets removed often lack accountability and transparency, and, in some forms, coordination could help power accrue to already very powerful companies—especially if there’s no independent oversight or possibility of remediation. ‘The pressure to do something can lead to the creation of systems and structures that serve the interests of the very tech platforms that they seek to rein in’, Douek has argued.

A circuit breaker is needed to stop the cross-platform spread of deceptive or misleading claims, but even the coordinated removal of posts and videos about issues like election fraud raises concerns about false positives and censorship. And if such an approach were applied globally, the platforms could draw criticism for imposing American norms of speech in other countries.

In any case, given the now embedded use of disinformation as a campaigning tool, a where-goes-one-goes-all approach to domestic disinformation is unlikely to be legislated. Any such measure would be interpreted by critics as collusion against a political party or message, even if it’s only labels on disputed posts. And it’s not clear that such interventions even work to halt the spread of misinformation.

The clash of local sensibilities with universal content moderation practices isn’t deterring some countries from developing national regulatory regimes. Australia, for example, is developing a voluntary code on misinformation with digital platforms. The European Union also has a code of practice on disinformation.

But around the world, claims of conspiracy often flow from the very top of government through friendly media channels. Those statements are then digested, edited and posted on YouTube, and the cycle begins again.

Content moderation is therefore only a partial answer to institutional and social failures. Companies like Facebook and YouTube shouldn’t be let off the hook, but better and more moderation can’t be the only way to halt the erosion of trust in elections.

As Douek has pointed out, what we consider a legitimate political campaign and what we consider manipulative is partly a social question, and not one for the platforms alone. That’s because at the centre of these problems are individuals. People’s political loyalties and desires, expressed by their clicks and shares, have helped spread the baseless idea of a voting machine ‘glitch’—albeit people who were being worked on by a fast-moving system of politicians, pundits, mainstream media and social media algorithms in a way that’s calculated to capture their emotions and attention.

And it works. Over the past seven days according to CrowdTangle, posts with the phrase ‘election glitch’ have received more than a million interactions on yet another Facebook-owned platform caught up in the disinformation cycle—Instagram.