Australia’s borders and migration system are now the most secure they’ve ever been. With the third wave of Covid-19 now raging in Australia, it seems clear that our international borders will be all but closed to new arrivals for many more months—perhaps even years. From Parliament House in Canberra to the streets of suburbia, Australians understand the profound direct economic impacts of Covid-19. The deeper and potentially multigenerational economic implications of Covid-19-constricted migration to Australia are not as apparent.

Many Australians romanticise their historical connections with the bush and economic successes built on the sheep’s back. Of course, the wool industry has been an important contributor to our nation’s growth. Still, permanent and temporary migration has long been the secret sauce in Australia’s economic success.

Skilled migration has been central to maintaining Australia’s economic growth for more than two decades, including the country’s successful traversing of the global financial crisis.

While we wait for the release of the Department of Home Affairs 2020–21 annual report, the

previous financial year’s data point to a significant migration problem with definite economic impacts. What’s more alarming is that these figures include only five months of the Covid-19 pandemic.

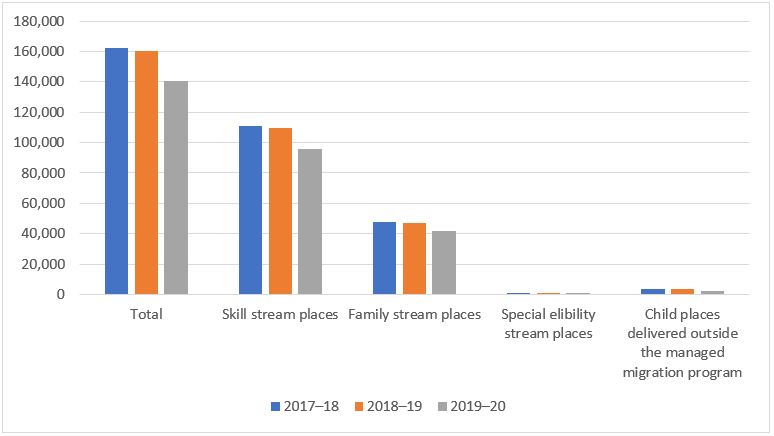

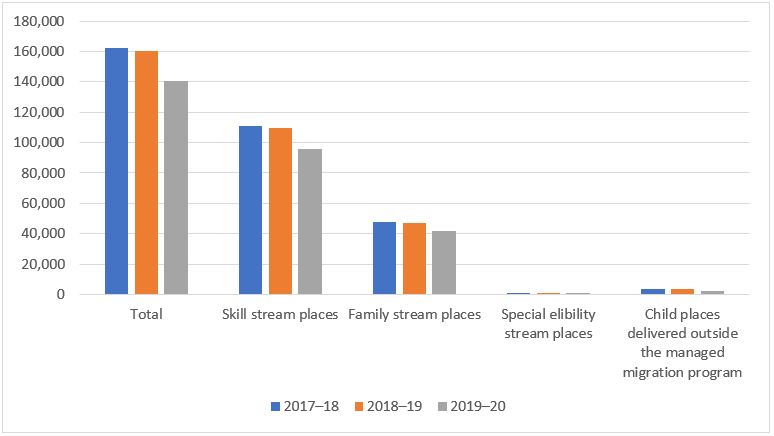

Australia’s permanent migration program fell by more than 20% from 160,323 in 2018–19 to 140,366 in 2019–20 (figure 1). The figures for 2020–21 will undoubtedly be even lower.

Figure 1: Permanent migration program and child places, 2017–18 to 2019–20

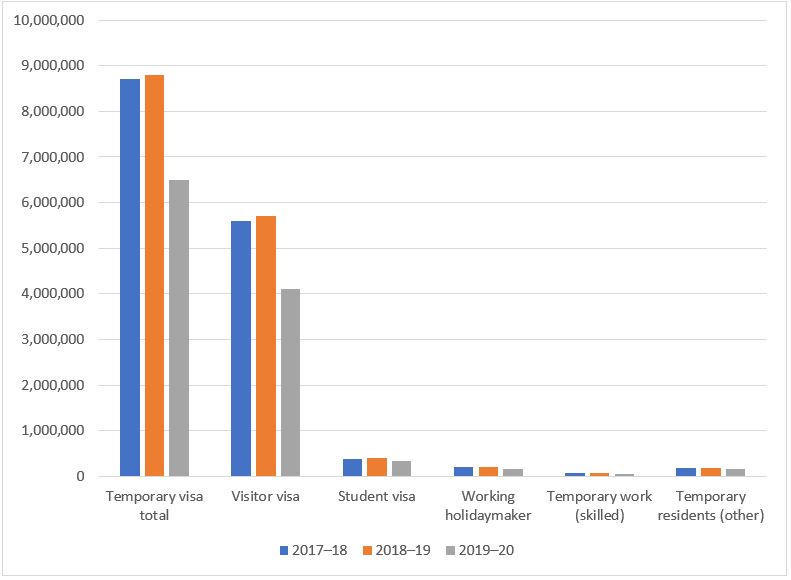

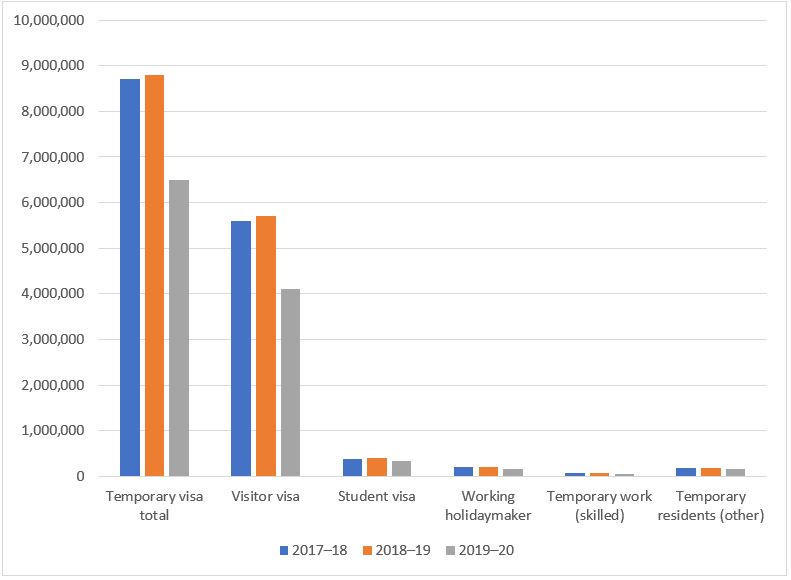

As expected, Covid-19 drastically reduced the number of temporary visas approved from 8.8 million in 2018–19 to 6.5 million in 2019–20, a reduction of more than 25% (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Temporary visas granted, 2017–18 to 2019–20

Temporary visa holders are critical to Australia’s migration program and economic success. This category of non-citizens, comprising students, holidaymakers and temporary workers, has kept Australia’s economy ticking away for decades. Some of them have brought new income streams into the economy, including in the tourism sector. Others, like temporary skilled workers, have provided Australian businesses with access to their much-needed talents. And some have offered cheap unskilled labour otherwise not available; many segments of the agriculture industry are reliant on this labour. Interestingly, before Covid this grouping also provided up to half of Australia’s permanent settlers each year.

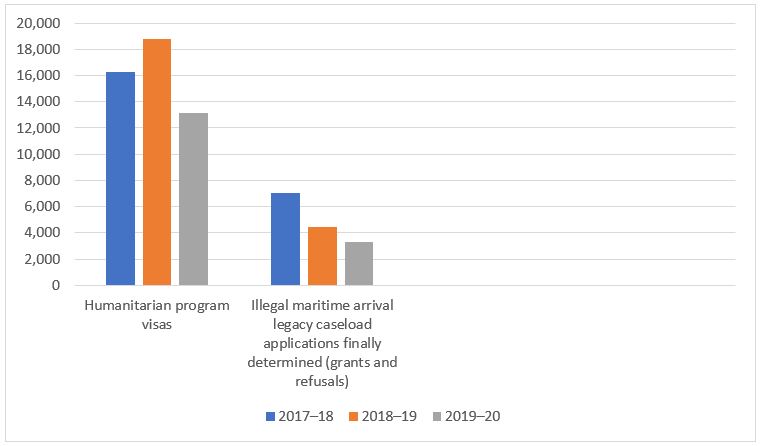

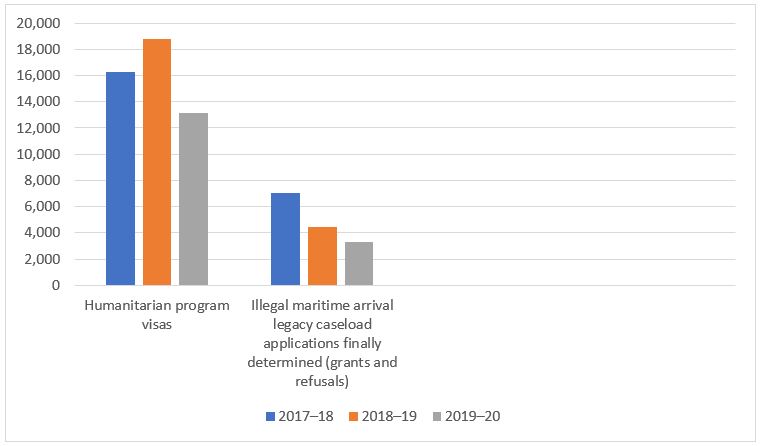

The refugee and humanitarian program entry fell by almost 30% from 18,762 in 2018–19 to 13,171 in 2019–20 (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Refugee and humanitarian visas granted, 2017–18 to 2019–20

These and 2020–21’s likely low migration figures are indicators of an emerging threat to Australia’s economic growth. Australia’s migration program is in trouble, and it may take several years and clever policy decisions to address the shortfalls. Even so, the problem will hinder the economic growth needed to lift Australia out of the Covid era.

What can the government do in the interim? Two possible options come to mind straight away. First, the government should consider addressing the so-called legacy caseload. Second, it could seize the opportunity Covid-19 brings to harness Australia’s large number of unlawful non-citizens.

In the second half of 2011, Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s government was under pressure over its policies on ‘irregular maritime arrivals’ and the growing number of asylum seekers in the country.

With limited options, the government decided that many low-risk irregular maritime arrivals, so-called boat people, would be released into the community on bridging visas. Following health, identity and security checks, they were released under strict conditions until their protection claims were assessed.

In August 2012, in response to an upsurge in boat arrivals and deaths at sea, Gillard re-established offshore processing of asylum seekers. Less than a year later, in July 2013, her successor (and predecessor), Kevin Rudd, established offshore resettlement. Those decisions led to the creation of a new cohort of people: the legacy caseload, or those already in Australia waiting for their claims to be processed.

Almost 30,000 people have been sitting in limbo for years on bridging visas that allow them to stay in Australia while awaiting an immigration decision. Without policy intervention, they’ll be waiting for years to come.

Given the impacts of Covid-19, the government could consider offering a one-time amnesty for all legacy cases. An exemption could be granted to applicants without criminal histories or adverse security assessments. Such an amnesty would provide permanent residency, subject to passing a character test, and a path to Australian citizenship.

As of 30 June 2017,

62,900 unlawful non-citizens were residing in Australia. The number has remained roughly constant over the past few years. Finding publicly available data on how long this cohort of unlawful non-citizens has been in Australia is challenging. In 2017, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection provided the Joint Standing Committee on Migration with the

most recent detailed (correct as of 30 June 2016) data on the issue, which showed that more than half of the unlawful non-citizens had been in Australia for five years or longer. Most of them had arrived on visitor visas, nearly 15% of which were student visas.

With Australia’s international borders now almost hermetically sealed, perhaps it’s time to bring this cohort of illegal non-citizens out of the shadows by offering them an amnesty to become full members of our communities.

Both measures make good economic sense. They would demonstrate the kind of pragmatism and big-heartedness that Australia prides itself on. These measures would also mitigate some of the impacts of the slowed migration program and reduce the not insignificant compliance costs for both of these cohorts.

Print This Post

Print This Post