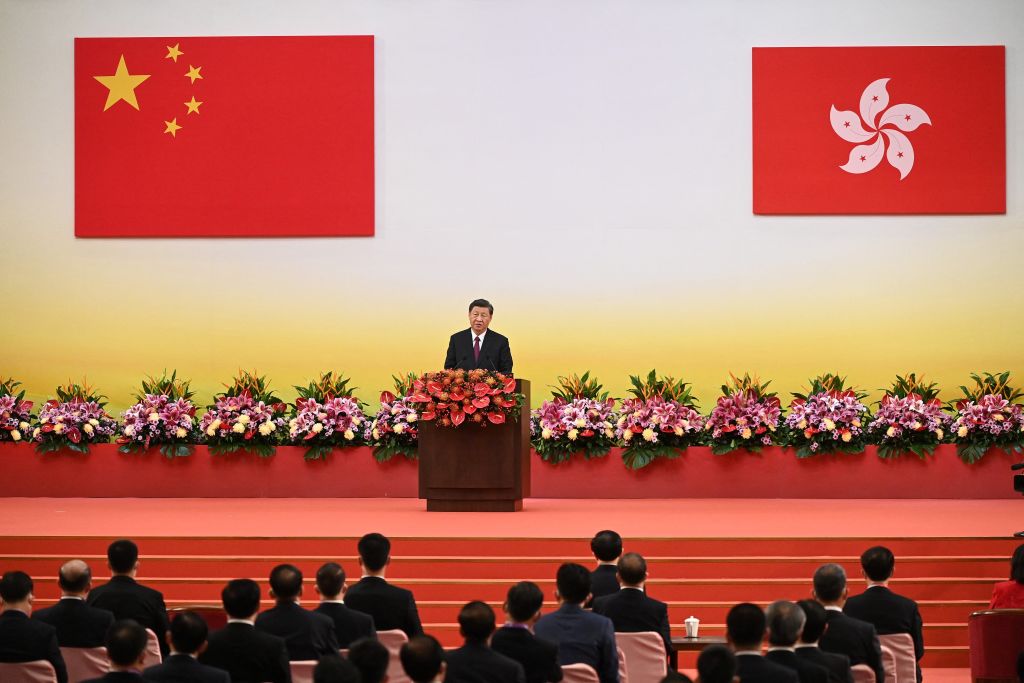

If norms exist in the Chinese Communist Party, perhaps Xi Jinping, the general secretary and de facto president of the People’s Republic of China, has established one by attending the inauguration of incoming chief executives. He last came to Hong Kong five years ago when Carrie Lam took up the post.

But his visit, whose length did not match the three days of 2017, perhaps from a fear of Covid-19 or a need to concentrate on mitigating its economic and social consequences on the mainland, has deeper significance.

For Xi himself, it is an opportunity to bang the nationalist and patriotic drums in this important year when he intends to continue for a third term in the trinity of top party, army and state posts. This reminder to the Chinese people that the CCP ended the ‘century of foreign humiliation’, which began with the ceding of Hong Kong to Britain, portrays Xi as the embodiment of the CCP’s success.

For others, the 25th anniversary is significant as a halfway milestone to 2047. Before the 1997 handover of Hong Kong, Deng Xiaoping, then paramount leader of the PRC, had promised ‘50 years no change’ (五十年不变) as reassurance that his policy of ‘one country, two systems’ would allow Hong Kong’s freedoms to continue and remain different from those on the mainland.

So, where does Hong Kong stand 25 years after the handover?

The answer is not where the people of Hong Kong and the British government hoped back in 1997. At best Hong Kong experiences ‘one country, one and a half systems’. ‘50 years no change’ was always a way of papering over unresolved differences or worries. The hope was that, by 2047, the PRC would have changed, and thus the gap with the Hong Kong system would have narrowed. Indeed the CCP has changed—for the worse—and the gap between past rhetoric and present reality has widened.

Every five years or so since 1997 the clash between Hong Kong’s and Beijing’s interpretation of ‘one country, two systems’ boiled over into protest. The issues were unsurprising: national security legislation (2003); national education (2012); electoral system (2014); and extradition arrangements, which then led to wider unrest (2019).

The wide scale demonstrations and street violence of 2019 convinced the CCP that its three ‘red lines’—no harm to national security, no challenge to the central government’s authority and the ‘basic law’, and no using Hong Kong as a base to undermine the PRC—had been crossed. In essence, they embodied the fear that Hong Kong’s protests and values might spill over into neighbouring Guangdong province and provoke unrest. The spear point of the CCP’s response was the national security law, or NSL, which came into force on 1 July 2020. The NSL centred on four crimes: secession from the PRC, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces. Their definitions are elastic—intentionally—and their enforcement ubiquitous. Currently, around 150 people are awaiting trial.

While maintaining the slogan of ‘one country, two systems’, the CCP has reached into its traditional playbook for ensuring control. No self-respecting and aspiring totalitarian regime can afford to ignore:

- Elections and political representation: These have become as meaningless as on the mainland. Changes to the system have eviscerated a once active opposition. The Legislative Council has become a body of ‘patriots’, a version of Beijing’s own National People’s Congress. 47 members of democratic parties are currently facing trial for the crime of organising a non-official primary election.

- Media: Chinese-language media has been the priority. At least four outlets have closed, from fear of the NSL. Jimmy Lai, who founded Apple Daily, has been painted as one of the big black hands behind the unrest. He is in prison. The English-language press in the form of the Hong Kong Free Press and the South China Morning Post stagger on, but they must be careful not to fall foul of the NSL, which punishes speech as much as action. Radio Television Hong Kong has been brought firmly under government control, and ‘inappropriate’ programs and journalists jettisoned.

- Education: This is an important area for Xi, who has long placed significant emphasis within the PRC on CCP control from the primary to professor levels. Student associations have been disbanded and textbooks rewritten. Teachers and professors considered unreliable have lost their posts.

- Civil society and non-governmental organisations: Fear and threats have led to the closure of civil-society groups, including trade unions and branches of foreign organisations such as Amnesty International.

- Law: This is perhaps the most crucial area, since Hong Kong’s prosperity has been built on trust in a legal system which underpins economic activity. Hong Kong’s common law system survives—even if there has been some fraying around the edges, such as attacks on the Bar Association, the abandonment of jury trials for NSL cases and greater political involvement in the appointment and selection of judges—for now.

Among other signs of reduced differences between Hong Kong and the mainland, there have been increasing interference and self-censorship in the arts and culture, an expansion of technological surveillance, and a greater presence and powers to operate for mainland security forces.

Hong Kong’s value to the PRC has been steadily diminishing. Its gross domestic product, once equivalent to over 18% of that of the mainland, is now under 3%. Its port and airport, while formidable, are matched by recently built facilities elsewhere in the south of the PRC. Shanghai, Shenzhen and other cities are increasingly important in meeting the PRC’s financial needs.

Yet Hong Kong retains value for Beijing. While the CCP might be happy to see Shanghai and Shenzhen take over the ex-colony’s financial role, there are impediments while the Chinese yuan, unlike the Hong Kong dollar, remains a non-convertible currency (and will for many years). Hong Kong has been a good place for Chinese companies to raise money. And it has proved useful for powerful CCP members as a safer place for their families and capital.

But Deng’s phrase of ‘50 years without change’ still haunts. It implies change after 2047. The CCP has set itself the ‘second centennial goal’ of becoming a ‘strong, democratic, civilised, harmonious and modern socialist country’ by 2049, the centenary of its founding of the PRC. Translated from party-speak, this means that the PRC is to become the world’s primary superpower in an international order transformed to its advantage and values. It is surely inconceivable that a CCP so committed to a narrative of nationalism and superiority would be happy for Hong Kong to retain much more than the merest vestiges of ‘one country, two systems’. For the CCP, Hong Kong must become no different from any other mainland city, including a move away from the common law system to legal consistency with the mainland.

This absorbing of Hong Kong into the mainland is partly what lies behind Xi’s emphasis on the ‘greater bay area’ plan, an intention to mould the 10 major cities of Guangdong province into an unrivalled economic and technological powerhouse. Hong Kong’s identity, population and culture would be subsumed and diluted into insignificance within the 126 million people of the neighbouring province. It is no coincidence that in the 28 June People’s Daily article announcing Xi’s visit, a large portion centres on Hong Kong’s future in the greater bay area. As 2047 looms, the CCP may be indifferent to whether foreign companies stay in Hong Kong or move north: if they wish to do business in the PRC, they will need a presence in Hong Kong or the mainland.

Sometimes it is the smallest details which reveal the state of things. The mainland press has assured the world that the Hong Kong police detachment of honour will no longer march in its traditional British fashion but with a mainland goose step. Political slogans, never a feature in Hong Kong, have been floating on boats through Victoria Harbour. Outside the Hong Kong police headquarters two banners spread different messages. In Chinese, there is the disconcerting message about a threat as yet unseen in Hong Kong, ‘Remember to report terrorists. The next victim could be you’ and in English, ‘United we stand’. One country, two audiences.