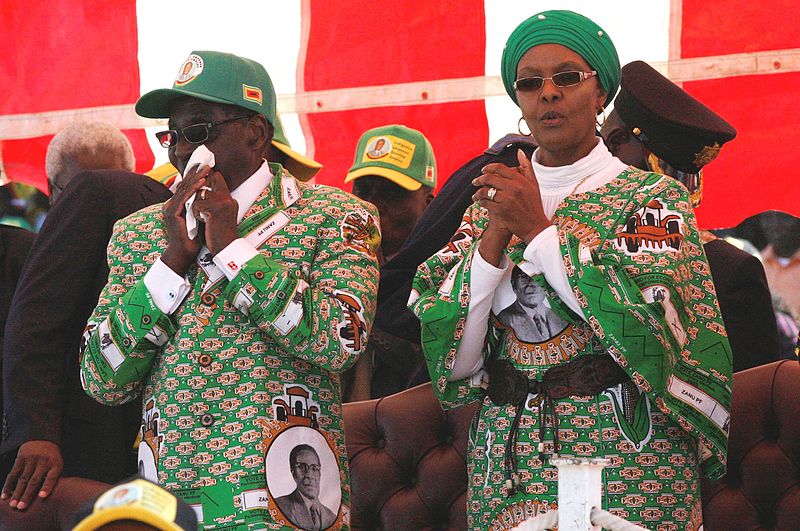

A year on from the coup that ousted Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe remains perched between piecemeal reform and old ways that are as intractable as they are destructive. That’s because the country is ruled by a clique with a partial and conditional commitment to change—and a total, obdurate determination to retain and enjoy power.

The ‘new’ regime can be viewed from different angles, but the nub of it is this: there’s a recognition that the economic fiasco of the last 20 years was suboptimal, but Emmerson Mnangagwa and his fellow travellers will burn the house down if they feel it necessary. Make no mistake, their will to power is every bit as intense as Mugabe’s—as is their belief that they own the country’s choicest fruits by right of conquest.

There’s no comprehending Zimbabwe without an appreciation of that mentality. Yet many fail to get it because they don’t read the country’s history. In 1979, at the height of the struggle against white rule, a diplomat who mixed frequently with Mugabe and other leaders of his party observed that ‘ZANU does not seem to attach much importance to the destruction caused by prolonged war’. They said they were content to see Zimbabwe ‘totally’ demolished if that was the price to be paid for preventing others from ruling it. That attitude has not changed an iota, notwithstanding the passage of 40 years and Mugabe’s departure. After all, the men who now rule wielded his hatchets for most of that period.

Therefore, the key question does not revolve around the prospect of a gradual transition to democracy, as the naive appear to hope. Rather, it is, in the first place, whether economic modernisation and international reengagement will be achieved without nudging the hypersensitive Zanu threat meter into the red. And that is not a matter of abstract rationality, but of perception—subjective responses that are also rooted in history and are shot through with not insignificant levels of paranoia, prejudice and entitlement.

The second red zone to watch is the margin between growth-compatible grand corruption of the type favoured by the Chinese and avarice of the nuclear variety for which Zanu has had an affinity since the 1990s. It’s not a question of whether Mnangagwa and company will continue to view Zimbabwe’s resources as a God-given right, but whether they can walk the line between controlled greed and madness.

The 12 months since Mugabe went have been a reflection of the attempt to marry limited change with non-negotiable stasis. Zanu’s dalliance with reform is as awkward as a politician’s jig, incorporating umpteen uncoordinated movements and unsightly contradictions.

The election campaign last August was largely violence-free, yet the vote count had numerous anomalies—and the evisceration of opposition protests was swift and brutal. The shooting of unarmed civilians and a roundup of opposition activists was a harsh reminder—in time-honoured, disproportionate fashion—that dissent would not be tolerated. It jarred horribly with Mnangagwa’s slick public relations effort, yet squared perfectly for those suckled on the nationalist iteration of monarchical absolutism—Zimbabwe’s alter ego to Europe’s divine right of kings.

The decision of Commonwealth and European Union election observers to withhold endorsement of the elections had much to do with the aftermath. Mnangagwa’s announcement of a commission of inquiry was meant to place the PR wreck back on its tracks, yet the process has also exposed the unreconstructed mindset that underwrites the regime. The commission was appointed unilaterally by the president—making it illegal under the constitution—its mandate appeared to prejudge the outcome, and its membership was a mix of well-regarded outsiders and clearly compromised insiders.

The hearings themselves have resulted in the subpoenaing of senior military commanders, but have also seen those whose hands are usually hidden flip a collective bird at Zimbabweans by providing explanations that expanded the boundaries of arrogance and implausible deniability. The chief of the defence forces, Philip Sibanda, told the inquiry that soldiers had ‘fired in the air but I do not believe any could have aimed shots at the civilians’. The tactical commander of the soldiers who pulled the triggers suggested that ‘militant’ members of the opposition had shot their own.

On the economy, away from the spheres in which farce and faux reform reign supreme, there are signs of genuine engagement: businesspeople report that it has never been easier to talk to government ministers, who are bending over backwards to attract investment; there’s a bid to apply laws governing the financial system more consistently; and there are indications that exports are beginning to increase in some sectors.

Yet there are no elements of life in Zimbabwe that can remain untouched by Zanu’s impunity and the ghosts of the ruling party’s past excesses. The government is living beyond its means, as it did under Mugabe, spraying about its largesse in order to keep the faithful happy and buy votes from the masses. The party’s backbone—the army and police—were given a 20% pay rise shortly before the elections.

The budget deficit has ballooned—and the government’s answer is a version 2.0, virtual variety of the profligate money printing that occurred a decade ago. It’s attempting to manage its overspending by issuing treasury bonds to the banks, ‘IOUs’ that are mirrored by electronic ‘dollars’ which are used to pay wages and buy goods.

Unsurprisingly, the effects have stoked—and been stoked by—fears of a return to the world-record hyperinflationary psychosis of 2008. Despite the government’s insistence that e-dollars (or RTGS, as they are known) hold parity with the US dollar, their value has plummeted and nervousness has skyrocketed among a population whose skittishness in the face of monetary shifts is as acute as Zanu’s sensitivity to political change.

Panic buying was sparked in October when the finance minister appeared to be preparing for an official devaluation of RTGS bank deposits. Meanwhile, many were confronted with an existential crisis when the purchasing power of the RTGS collapsed, rendering medicines and other basic commodities unaffordable. Zimbabweans’ sense of déjà vu was further fuelled by a near-simultaneous outbreak of cholera, which infected 8,500 people and killed 50 in the capital, Harare.

In mechanical terms, the only way Mnangagwa’s administration can climb out of its economic hole is to take the pain and slash expenditure while increasing revenue in ways that don’t sting investors. But the economic conundrum is not simply a question of top-down mechanics. The turmoil of October is a reminder that relational factors from bottom to top matter, too.

Just as the domestic market is dubious about promises to repay government bonds and assurances over the value of RTGS deposits, foreign investors fear that their hard currency imports will be converted to RTGS or that they will be prevented from remitting their profits. The government needs to rebuild trust, in addition to imposing fiscal discipline.

That’s a tough ask for the same group of individuals who have shredded the country since 1980—a fraternity that will continue to loot, will continue to be tetchy about the merest hint of dissent, and will continue to patently despise the notion that it requires the consent of the people to govern.