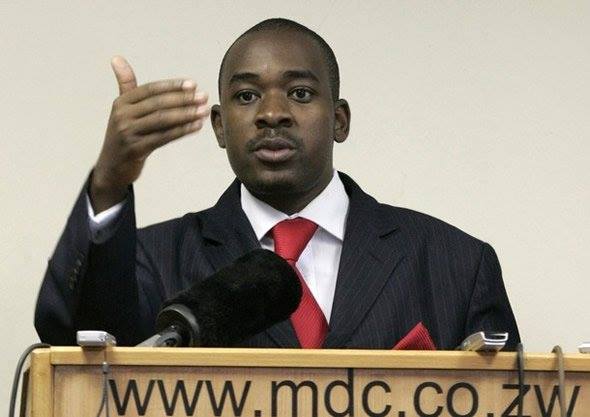

On 10 August, Movement for Democratic Change Alliance President Nelson Chamisa made it to the courts 30 minutes before the deadline to lodge his application challenging the results of Zimbabwe’s presidential election. The electoral commission declared Zanu-PF’s Emmerson Mnangagwa the duly elected president on 3 August. However, his inauguration, scheduled for 12 August, was deferred pending the Constitutional Court’s decision.

The Constitutional Court has 14 days to hear the case and settle on a verdict, which is final. There won’t be any recount of the votes, as that would have had to be done within 48 hours of the results being declared.

It is incumbent on the applicant to prove that election irregularities actually affected the result. As NGO Veritas explains, ‘[T]he Electoral Act … is not clear about the grounds on which a presidential election can be successfully challenged’. While the Constitutional Court begins to sift through the piles of petitions from both sides, there is anxiety and suspicion that Zanu-PF will interfere with the court’s judgement. The opposition in Zimbabwe has a long history of petitioning polls, with no success.

Amid the mayhem, the army continues to make its presence known in the townships and villages, violently cracking down on opposition supporters. Senior officials haven’t been spared—a senior MDC member and former finance minister, Tendai Biti, tried to seek asylum in Zambia, only to be handed back to the Zimbabwean authorities and later appear in court. Biti was eventually granted bail, but his lawyer and other senior MDC leaders are still in prison for assisting him to flee. Mnangagwa has claimed that he intervened to ensure Biti’s release.

Two days after the elections, what was left of Mnangagwa’s international reputation as a reformer lay in tatters as six protestors were shot dead by the army. His new-found friends in the West have come to realise that there’s more continuity than change in his response to political dissent. His re-engagement messaging became meaningless once confronted with legitimate challenges and protests as he reverted to familiar tactics of suppression.

The international community was quick to condemn the post-election violence in joint communiques. UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres spoke by phone to both Mnangagwa and Chamisa—something that has never happened before in Zimbabwe. The Australian government added its voice, urging Mnangagwa to be more open and seek justice for the victims of the violence.

The South African and Kenyan presidents sent Mnangagwa congratulatory letters, as did Botswana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola, preparing to attend his inauguration. African nations, through their observer missions, declared that the election had been much freer and more peaceful than those observed under Robert Mugabe. However, they did denounce the post-election violence perpetrated by the army.

As long as the West and the Africans don’t see eye to eye on the way forward, Zimbabwe is doomed to be a military state for a long time to come.

The MDC Alliance petition cites many irregularities, including mathematical errors that affected the results. Chamisa also argues that the election didn’t adhere to constitutional requirements, such as access to state media and prohibitions on the use of food handouts and the misuse of state funds—issues that have been the bane of Zimbabwe elections since 2000. Chamisa wants the court to reverse the Electoral Commission’s declaration of Mnangagwa as the winner or order a rerun. Zanu-PF has dismissed the petition, saying that Chamisa missed the deadline.

Support for Zanu-PF among Zimbabweans is based on factors such as the liberation struggle and land distribution (which creates a dependency associated with control of resources such as agricultural inputs by the state), combined with a history of violence against people who oppose the state in the rural areas where Zanu-PF wins.

The opposition, born out of the trade unions, has its stronghold in the urban areas. Employment has declined in those areas because of a reconfiguration of the economy that has made the public sector the main formal work sector. To work in government, you have to owe allegiance to Zanu-PF.

It is highly unlikely that the junta will allow Chamisa to win this election even if there is a rerun. Mnangagwa has already dismissed a government of national unity.

The support Mnangagwa received from the UK and the EU and future support from international financial institutions such as the IMF are based on the legitimacy of a free and fair election. Until that’s resolved, the chances of economic assistance are bleak. Mnangagwa’s government will need to provide both political and economic reform as security for investors and the IMF.

As Donald Trump moved to extend sanctions on Zimbabwe, the deputy vice president and recently retired army chief, Constantino Chiwenga, responded that he was disappointed; he was in Russia meeting with Russian investors.