The recent dialogue between Hugh White and Peter Jennings on The Strategist makes us all ask where we stand on the Sino-Japanese relationship. Statements by President Obama emphasise that the United States takes its security partnership with Japan seriously, while Prime Minister Abbott was reassuring towards Prime Minister Abe during the latter’s recent visit to Australia. In many ways, those statements are wise and reflect the gravity with which both the United States and Australia view their treaty obligations.

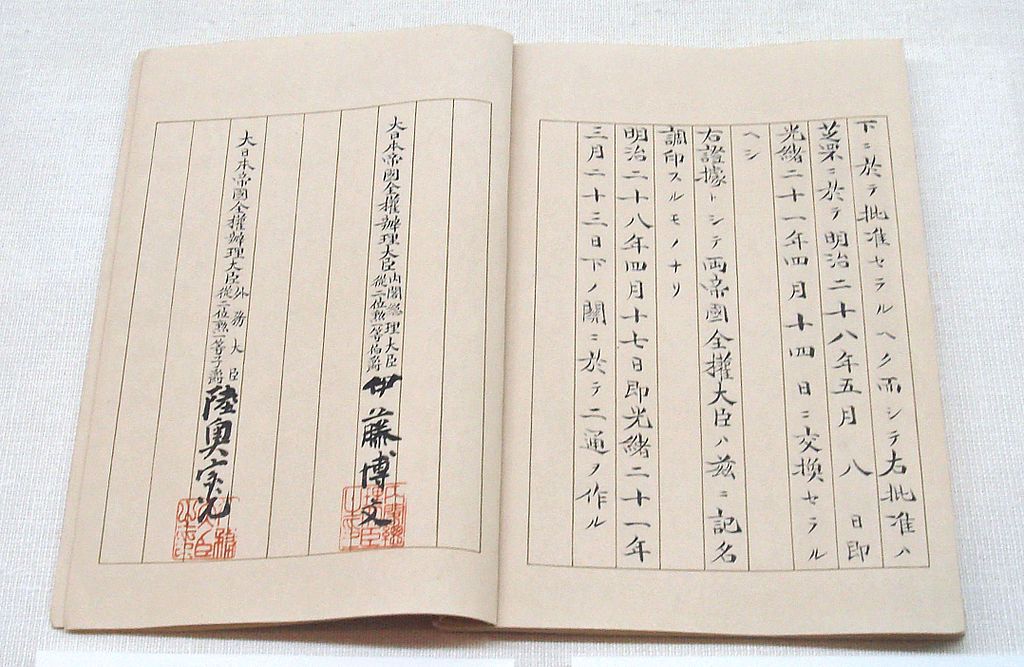

There is, however, another side to this question—what do the Chinese think about the issue and are we handling them in the best possible way? Before we make up our minds simply to defend the status quo in the western Pacific right down to the last detail, it might be prudent to examine the diplomatic basis on which security rests. We know about the US–Japan Treaty of Mutual Co-operation and Security concluded in 1960, and we certainly know about ANZUS, concluded in 1951. But we may be less familiar with the principal agreement between Japan and China in the western Pacific: the Treaty of Shimonoseki (Japanese version pictured), concluded in 1895 and still partly in effect. 1895 was a good time for Japan to insist on a treaty that expanded the area under its control, and a poor time for the Chinese to negotiate on behalf their interests.

The principal European imperial powers had been giving China a hard time through the 19th century. The British Opium War against China looks absurd today, with the British sending in the Royal Navy to blast the Chinese defences because the Qing Emperor refused to allow the commercial entry of opium from the East India Company in the 1840s. There were several other conflicts in which a weak China gave way to the formidable military power of foreign states, resulting in a series of agreements (at least 22 of them) termed by the Chinese the ‘Unequal Treaties’. The most consequential of those conflicts was the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95, which, after a Japanese victory, was concluded by the Treaty of Shimonoseki.

That treaty gave Japan Taiwan, the Ryukyu Islands and possibly the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, although the treaty isnt explicit on this point. The Japanese believe the islands are included while the Chinese do not. The Japanese lost Taiwan to China after World War II, and the United States administered the Ryukyus and the Senkaku/Diaoyu group from 1945 until 1972, when Japanese sovereignty was restored. Since then the Chinese have pressed their claim, based on their view of history, to have the Senkaku/Diaoyu group returned to them.

The Japanese response has been to stand firm, and to strengthen the national claim by buying three of the five major islands of the group from a private Japanese owner. There has been no indication of Japanese readiness to step back on this issue and discuss the return of those islands to the Chinese. Indeed, all the indications have been in favour of a willingness to go to war to defend the Japanese claim. That response flies in the face of growing Chinese military strength, and Chinese public opinion which, in the 21th century, remains highly critical of Japan.

The issue of the balance of military strength is particularly disturbing, partly because of the increase in the range, sophistication and destructiveness of Chinese weaponry, and partly because of the proximity of the islands to the Chinese mainland. At 330 km from the Chinese coast, and 170 km from Taiwan, they, and the seas around them, can easily be subjected to intense attack by Chinese forces based on the mainland.

That in itself isn’t a reason for giving them to China, but when set into the wider contexts of economic relations, strategic geography and historical experience, one has to wonder whether the islands are worth running the risk of a war over, to Japan, the United States and possibly other allies of the US such as Australia. The question is all the more salient when one considers the fact that the islands are uninhabited. The seas around them may, or may not, be covering hydrocarbon deposits, but at present they are of economic significance only for fishing.

Before both sides in the dispute get into such a level of confrontation that a war seems thinkable, would it not be better for them to step back, relax a little, and think more positively about how they might resolve this dispute peacefully? Given China’s memory of the ‘Unequal Treaties’ of the 19th and 20th centuries, might it not be time to revise what was done in a markedly different context in 1895? And might it not be better for Japan’s allies to have a little less to say about willingness to support it without their having a decisive voice in heading off a possible crisis?

Robert O’Neill was the head of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre from (1971–82), director of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (1982–87), and Chairman of the IISS (1996–2001). Image courtesy of Wikipedia.