The world is less stable and less predictable than it has been in generations, marked by profound and disruptive change, with the unsettling promise of more to come.

The Middle East has been rocked by an unexpected war in Gaza, Russia continues its unjust war against Ukraine, and persistent tensions in the South China Sea threaten to flare at any moment. Malicious cyberattackers are threatening critical infrastructure and stealing intellectual property. The information environment is awash with increasingly sophisticated disinformation that governments and online platforms are struggling to keep up with. The effects of climate change bring urgent challenges to all nations, but particularly to Australia’s partners in the Pacific and Southeast Asia.

Unsurprisingly, Canberra is battling burnout as it tries to keep up with the cumulative effect of concurrent, compounding crises—many of which began as the world was still recovering from the shock of a truly global pandemic. Politicians and senior public servants have only so much bandwidth to deal with the world’s increasingly frantic pace.

If anything, the speed of change and the complexity of challenges will only increase in the coming years.

The world is on the verge of revolutionary technological change. Artificial intelligence is just one of a suite of game-changing developments that governments must deal with—each emerging technology brings enormous potential benefits but also risks of a nature humanity hasn’t faced before. While the digital era has brought great benefits to societies and economies, for democratic nations each technological evolution adds to the already long list of domestic and international security challenges that need to be managed. Crucially, as threats to countries’ security, economies and stability evolve, so must their forms of global engagement.

Australia is a more influential player than it has ever been in international affairs. We need to embrace this responsibility, starting with ensuring we have the right architecture to help deal with the hyperspeed of global developments. While Canberra’s bureaucracy often prefers the status quo, it’s vital this architecture is continually assessed to ensure it remains fit for purpose. The government—and the public—need to have confidence that Australia can execute the integrated statecraft needed to navigate today’s increasingly complex international environment.

The review of Australia’s intelligence community that’s now underway—as long as it is delivered with ambition so it remains relevant years from now—is one tool that will help prepare the government to confront the speed of global change. In the current environment, maintaining a strategic and technological edge over our adversaries, remaining a sought-after and valuable partner that can keep pace with bigger and better-resourced intelligence communities, and attracting and retaining top workforce talent (for which industry is also fiercely competing) will continue to become harder.

Both the domestic and international stakes are higher for this intelligence review than the terms of reference let on, so the review’s output should be watched closely. But it likely won’t look at a gap in Australia’s security architecture that has been filled in almost all counterpart nations—a dedicated and autonomous national security adviser (NSA). An Australian NSA would report to the prime minister and speak publicly with a trusted voice both internationally and domestically on Australia’s most pressing interests and priorities.

Without such a position, Australia is missing out on a seat at the table at key global meetings, which provide the best opportunities to exercise the kind of influence we want, need and deserve. What’s more, the lack of an NSA means the government lacks an authoritative representative who can help set the tone and focus of our strategic communications across all international security issues.

Most countries—including our most important partners—have an NSA. These roles are as senior as it gets, often equivalent to a department head or sometimes even a minister. NSAs have the ears of their leaders, often travel with them and are always available for briefings and policy advice. Critically, most NSAs also maintain their own remits of policy work and their own busy travel schedules separate from their presidents or prime ministers.

NSAs are increasingly in the public eye, giving interviews, press conferences and speeches at home and abroad, issuing statements and adding their name—and their country’s imprimatur—to communiqués alongside their counterparts from other nations. That provides a crucial avenue for collectives of countries to express shared concerns or endorsement.

They travel extensively and convene gatherings. This is a vital need for Australia given that part of our growing influence comes through our membership of international groupings such as the Quad, AUKUS and the Five Eyes, and our deepening networks across the Pacific, Southeast and North Asia. Post-Covid-19, NSAs from multilateral groupings such as NATO have held major gatherings to discuss everything from deterrence to technological innovation to climate change. Minilateral NSA meetings, such as the ‘Quint’ of the US, UK, France, Germany and Italy, and the public statements and media that can accompany them, are proliferating, including across our region.

Our Quad partners, the US, Japan and India, all have dedicated NSAs or an equivalent, as do our AUKUS partner Britain and Five Eyes partner Canada. So do South Korea and a number of our most important ASEAN partners, including the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand. The role is standard across Europe and the Middle East. Some, including our Quad partners, also have senior NSA deputies who share the travel and convening load.

The remit of a typical NSA is broad, covering regional tensions and conflict, critical technologies, economic security, nuclear issues, deterrence, counterterrorism, hybrid threats, climate security and more. A large part of their value is that NSAs can weave together all aspects of global security, addressing evolving and emerging challenges—in close coordination with partners and allies.

India’s influential NSA, Ajit Doval, a former intelligence and police chief, travels with Prime Minister Narendra Modi but is empowered to convene, negotiate and implement policy on the prime minister’s behalf. In the past year, he has brought together NSAs from the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and BRICs countries, met with NSAs from the Middle East and continued his long-running cooperation with his American counterpart to build US–India links in critical technologies. All the while, he contributes to the public debate in India on issues ranging from counterterrorism to cybersecurity and AI.

US NSA Jake Sullivan and his deputy are, as one would expect, incredibly globally active. Earlier this year the busy Sullivan got generative AI on the agenda of an already packed G7 leaders’ meeting in Hiroshima by calling his counterparts. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was present as an observer. AI was a surprise last-minute addition, joining the long-tabled issues of economic security, China and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

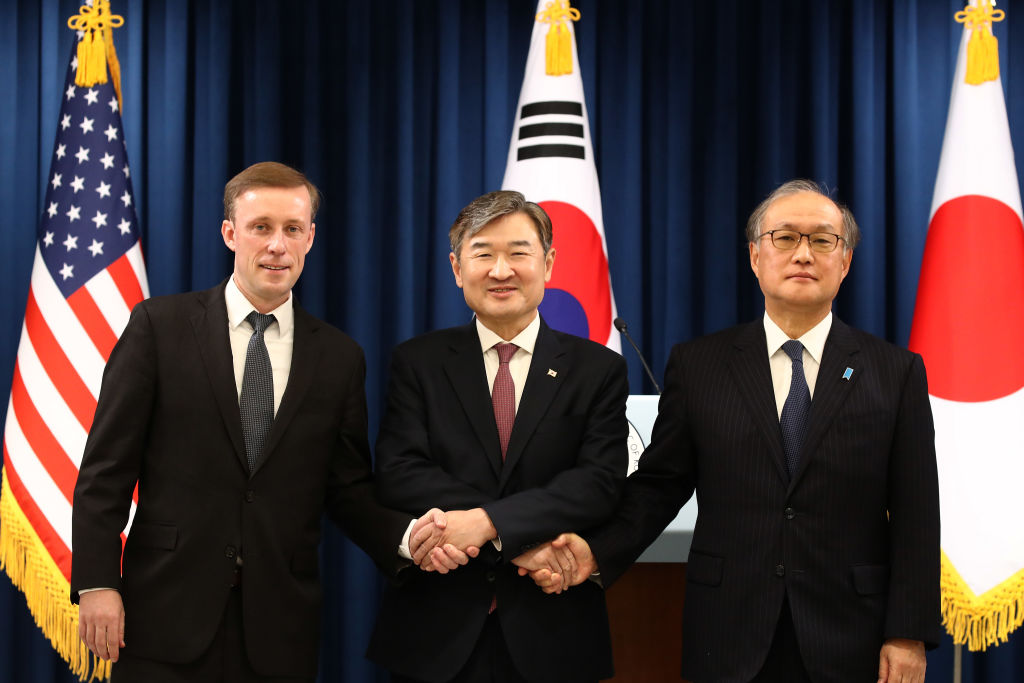

NSAs in the Indo-Pacific are deepening their cooperation. The NSAs of the US, Japan and the Philippines held their first joint talks in June, at which they agreed to strengthen security cooperation and discussed key challenges such as China and North Korea. Many decisions are made before world leaders actually meet. This year’s Camp David summit with the leaders of Japan, South Korea and the US was a historic achievement and astounding for anyone who knows the history of disagreements between the two Asian neighbours. But the fact that these countries were growing closer on security would have been less of a surprise to anyone who’d tracked the public meetings of their three NSAs in 2022 and 2023. On 8 December, they met yet again in Seoul.

Amid this boom in engagement, Australia is not in the room.

Of course, we have senior national security officials, intelligence chiefs, ambassadors and influential ministerial advisers. But none fill all the criteria of autonomy, ability to speak publicly, having a policy focus and dedication to the particular relationships needed with counterpart NSAs.

Ambassadors already have well defined, in-country remits. Intelligence chiefs have the right seniority and many have extensive global links, but they can’t lead policymaking and already have a world of counterparts they need to engage with regularly. Ministerial advisers are influential domestically, with a senior adviser in the Prime Minister’s Office traditionally seen as our closest equivalent to an NSA. They have the prime minister’s ear, including on overseas trips, and regularly talk to partners. But they don’t speak publicly, don’t have their own policy remit or voice, don’t travel separately to the prime minister and don’t put out joint statements. Even when invited, they simply can’t be present at the increasing number of NSA meetings where trust and personal relationships are built and decisions are made. Most importantly, because of these many limitations, they are not seen to be an equivalent or accessible counterpart by our global partners. In the busy and complex international environment we’re in, it’s a terrible time to be at such a disadvantage.

Australia has circled this issue before. In 2008, Kevin Rudd created an NSA position, originally filled by Duncan Lewis, who went on to head the Department of Defence and later the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation. While the appointment was prescient, the position was put in the public service and lacked the legislative backing, authority and staff needed to be truly effective. It eventually folded. Australia is well placed to learn from this experience.

Today, Australia needs a secretary-level NSA who, from within the PMO, should report directly to the prime minister. Some might argue that the role should be placed in a department and under the secretary, but that wouldn’t work. The role would quickly become subsumed by a single department’s hierarchy and interests. It would also lack ongoing access to the prime minister, thereby failing to become an NSA equivalent to those of our key partners.

An Australian NSA would need a small secretariat (an individual wouldn’t be able to keep up with other dedicated NSAs and their offices). This team could begin with a handful of national security and intelligence experts seconded from government. The role needs to be markedly different to that of parliamentary advisers, with its own clear and public remit. It must include freedom to travel so the Australian NSA can meet with and convene their counterparts from around the world. It must be public facing and—like influential NSAs in the Indo-Pacific—must speak to both domestic and global audiences to help explain developments and the challenges the region and the world are facing.

Australia in 2023 is a substantial regional power with global interests. We should have the personnel commensurate with this status. As the urgency and implications of regional and global security issues increase, a dedicated NSA would allow Australia to short-circuit bureaucratic processes to get a seat at the tables where key decisions affecting us, and our region, are taken. It would amplify our voice in prosecuting our strategy to the audiences we most need to win over.

It’s not in Australia’s interests for this gap to remain unfilled. There will be some concerns about turf encroachment and some risk-aversion in parts of the Canberra bureaucracy. That’s par for the course when major new roles are considered. Some might attempt to dismiss a dedicated NSA option by arguing that there appears to be a lack of appetite in this government to do more on international and economic security. But it would be virtually impossible for any senior official to argue that risk-aversion will carry Australia through the challenging years to come.

The prime minister should look overseas to our close partners and allies for their advice and input. One can assume that, despite limited resources and their own competitive bureaucratic structures, there are reasons they value and keep these senior roles. One reason likely to be raised is that many of their NSAs can speak up on security matters when their political leaders don’t wish to do so. When a country like China breaches international rules and laws but leaders and ministers don’t want to risk fanning political tensions, Australia’s partners can issue NSA-led statements that are viewed as consequential while less confrontational. Australia doesn’t have this option. As long as the NSA is senior and influential, they also give many countries another valuable avenue to access world leaders and other senior ministers when needed.

In a period of overlapping crises, in which global security policy is ascendant and every country is clamouring to assert its narrative, Australia needs to seize every possibility to shape conversations and outcomes—in private and in public. Having an NSA would allow the government to better capitalise on the huge investments we are making in AUKUS, in mechanisms like the Quad and in stepping up our regional relationships in Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

As we enter 2024 with global conflicts and the likelihood of more unforeseen security events, Australia’s ability to navigate the world would be strengthened by appointing an influential and autonomous NSA who can work hand in glove with their global counterparts in tenacious pursuit of our interests.