Australia’s coup culture isn’t about generals rolling over politicians and tanks rolling through the streets. The Oz coup culture is concerned with what political party rooms do to unpopular leaders.

The willingness of parties to lop off a prime minister’s head has become part of Australia’s international image. Think koalas, kangaroos, surf beaches, the Opera House and PMs wiping away a tear as they depart the ministerial courtyard.

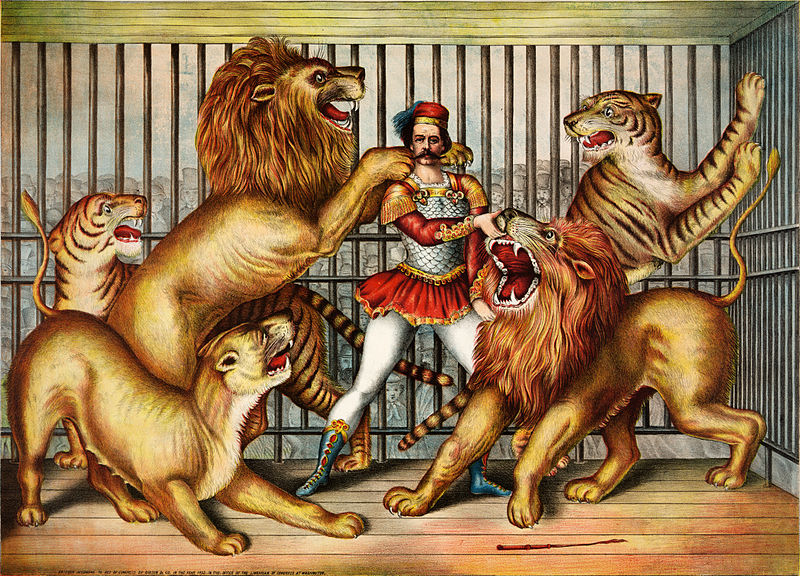

Where once we mocked Fiji as ‘coup-coup land’, Canberra is now the town of the caucus coup carnival. Perhaps that word ‘carnival’ should be rendered as ‘carnivore’.

The central drama of 2015 was Turnbull replacing Abbott. In the same vein, 2013 will be remembered for having three PMs and 2010 was when Julia pole-axed Kevin.

This column is merely to prod the nature of that carnival.

The Oz coup culture is brutally efficient. Stress efficient as much as brutal. Perform or perish. See this previous column arguing that caucus culling is harsh business with high purpose. Australia is entitled to the best years of the best leader on offer. There’s just the matter of getting the right leader.

Politics, the most inexact science, builds from failure as much as success. A bit of brutal efficiency is classic Australian pragmatism.

For something that can so alter politics and government (and, as Turnbull is attempting, tone, temper and tide) the internal leadership challenge is one of the strange holes in our political understanding and theorising.

Each coup is dramatic and traumatic. The ground shakes, lightening crashes, knives flash and suddenly the caravan gallops away at speed from the carnival scene.

After a successful overthrow, a shroud is thrown across much of the previous leader’s works and a public forgetfulness attempted. After a failed attempt, the public talk of reconciliation and rebuilding goes along with private recrimination and retribution.

Having stood close to many a Canberra carnival, I used to have a political version of the Chekhov rule—as each unhappy family is different in its own way, so is each coup unique.

Really, though, much is the same even as the cast changes. The action is always messy, the agony is always fresh and those who triumph always promise to make the world anew. Then the choosing and the chasing and the chastening begins… Inside the caucus there’s never any forgetting. Even less forgiveness.

Professor Rod Tiffen has provided handy guides to the coup culture (72 leadership coups in state or federal political parties since 1970) and seven points on the media’s role when the carnival rolls into town.

Rod offers a framework for an understanding that coups do much more than make and unmake leaders. These unusual moments can make or destroy the careers of many of those in the caucus who decide the leader.

The drama isn’t just regicide. This is the collective and individual agony of politicians having to make a decision that will define their own future, both as people and as party.

The individual dimension of fear and ambition is what throbs through this key point. Only a few constant truths apply: it’s always personal, and there’s always a deal.

Isaiah Berlin captures that in Political Judgement when arguing that the politician’s art has few ‘laws’ and little ‘science’. No wonder they get frantic. Nothing to steer by but everything to play for, with an ability to count as a survival skill.

One reason so many in caucus are prepared to confide in journalists (usually on background) during the build-up and the coup crisis is the psychological need to talk it through. This isn’t just sending signals via media to other members of caucus.

The MP agonising over scenarios and the shifting tide of party room numbers has to guard every word uttered to fellow politicians.

The reporter, by contrast, is happy to play confidant and promise anonymity in return for the right to use the information. In the making of a coup, the power relationship between pollie and hack is more equal than usual. Both are peering into the unknown and the pol’s power, even information dominance, is much weaker.

Part of reading the runes is determining which hacks are on the drip from which factions or players and reading their stories accordingly.

In the strange symbiosis of politician–reporter relations, the plotting and playing out of a coup is one of the most fraught. The personal stakes are so high for every plotter and those seeking to block the plot. Who else can they talk to relatively openly but that ‘friendly’ member of the Gallery?

Being on the wrong side of a challenge—backing the wrong horse—is the ultimate piece of poor political judgement. Not even able to be on the winning side inside the party room! Pick well and the ministry beckons. Go wrong and be marooned on the backbench or heading to the exit.

Many political careers pivot or plunge on the choice made in a leadership balance. No wonder politicians obsessively plot the numbers in caucus. If the moment of choice comes, they’re voting on their own promotion or demotion as well as selecting the leader.

In a leadership ballot in a party room, few can hide. They must choose and be branded by that choice.

Get it right and zoom into the ministry, get it wrong and wait for the punishment.

The issue of having to declare allegiance is at work in the Labor Party’s new spill rules which aim to control the brutal efficiency of the carnival: 60% of the party room must sign a petition calling for a leadership ballot. No quick show of hands here. The names have to be signed on the paper. Much safer to put the knife in anonymously via the Gallery.