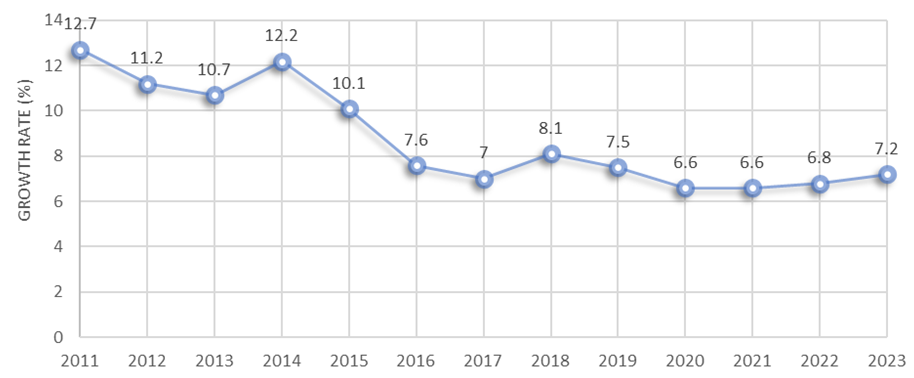

During China’s high-level ‘two sessions’ (两会) meetings this year, defence ministry spokesperson Tan Kefei (谭克非) disclosed that ¥1.58 trillion ($338 billion) had been allocated in the 2023 national budget for defence, up 7.2% on the previous year. The central government allocated ¥1.55 trillion ($332 billion), continuing the trend of defence budget escalation for three consecutive years. The balance came from local-level governments.

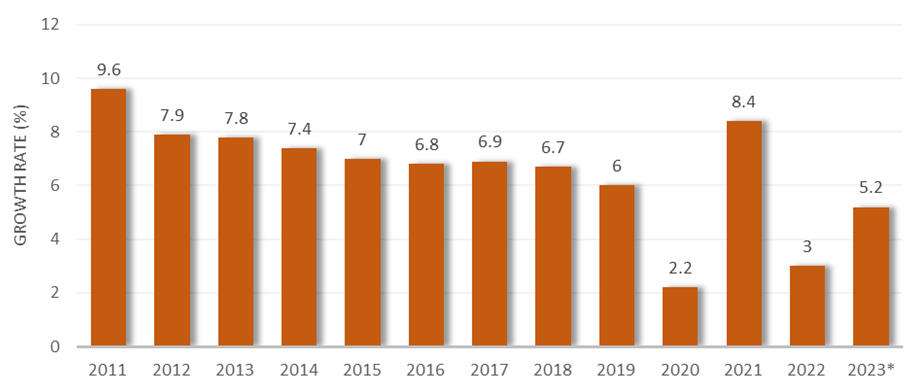

Over the past decade, China has raised its defence spending each year by a higher percentage than its annual GDP increase as it strengthens its armed forces.

Figure 1: Annual growth rate of China’s announced defence budget, 2011–2023

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China.

Figure 2: Annual growth rate of China’s real GDP, 2011–2023

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2011–2022); International Monetary Fund (*2023 forecast).

Beijing has portrayed its military expenditure as ‘reasonable (合理)’ and ‘moderate (适度)’ compared to that of Western powers such as the US and insisted that China is a responsible global actor committed to preserving peace. Those claims are belied by China’s militarisation of the South China Sea and extensive combat-readiness patrols and drills around Taiwan.

China’s surge in military capability, irrespective of the impact on territorial disputes, has significantly bolstered its political leverage and tilted the regional military balance in its favour. Its armed forces are ambitiously pursuing top-to-bottom modernisation and diversification that includes what Beijing refers to as ‘intelligentised warfare’, or using AI to control the will of potential adversaries at all levels.

China’s aim is to equip its military with cutting-edge weapons and to ensure that its land, air and maritime forces can work jointly with elements involved in space, counterspace, nuclear, electronic and cyber warfare. Beijing’s efforts have fuelled a progressively more volatile and competitive security landscape, forcing countries that are heavily reliant on trade with China to navigate the sometimes conflicting demands of their strategic interests and economic growth.

The eroding credibility of US conventional deterrence amplifies the risk of conflict. It increases the possibility that a more assertive and audacious China will seek to unilaterally alter the status quo in the Indo-Pacific by threatening to use, or actually using, multi-domain anti-access/area-denial strategies to curtail US power projection and operational effectiveness.

China’s military forces have two primary components: the People’s Liberation Army and the People’s Armed Police. The PLA, which includes the army, navy, air force, rocket force and strategic support force, constitutes the central and foundational element of China’s military capabilities. The PAP, which includes the internal guard, border defence, coastguard and specialised tactical units, has been excluded from the military spending equation on the premise that its operations are limited to domestic security.

While the reported percentage of China’s military spending as a share of GDP has remained relatively steady for many years, it can be assumed that additional money is being spent in classified areas.

As noted in a previous edition of ‘China military watch’, the official figures in China’s defence budget may not reflect the true extent of Chinese military spending. The lack of transparency over the levels of military spending that are acknowledged and the rapidly expanding capability of China’s forces only add to the opacity.

Historical spending patterns outlined in China’s 2019 defence white paper indicate that equipment has accounted for the largest share of the defence budget in recent years, ahead of personnel, training and maintenance. The 2017 military reforms were intended to produce a more balanced force, in part by streamlining and reducing the size of the army through cutting-edge technologies such as enhanced armour and improved logistical support. Beijing’s aspiration to become both a land and sea power has driven its pursuit of modernised battalions that surpass the capabilities of the traditional mechanised infantry battalions. Despite these efforts, however, the army has maintained its position as the primary beneficiary of military spending due to China’s longstanding continental defence history.

Chinese military scholars and experts have been talking about the seemingly lower 2023 defence budget, when it’s calculated in US dollars, compared with the previous year. They note that this is happening while most countries are scaling up their military expenditure. On closer examination, it’s not clear what accounting method was employed—purchasing power parity or the market exchange rate—and how expenditure was converted to real output or capacity.

At the root of this confusion lies China’s lower labour costs, which mean its currency’s military services purchasing power surpasses both its purchasing power parity and market exchange rate values. Estimates of money spent fall noticeably short of covering China’s military capabilities. That’s because China’s military industry operates under a predominantly state-owned model and therefore functions differently from a market-driven model in terms of costing and equipment procurement. The production and pricing of military equipment in China adhere to the principles of cost preservation, low profits and tax exemptions. Notably, research and development expenses, design changes, process improvements, equipment updates and tooling procurement all undergo separate procedures and are not included in the cost calculation.

China’s defence spending exhibits remarkable efficiency. With its formidable manufacturing and labour-intensive productivity growth during the economic reform era, the country has established a self-reliant and cost-effective industrial chain spanning the entire spectrum of weapons development, batch production and deployment of weapons and equipment. This removes the need for time- and resource-consuming purchases from abroad.

Having the world’s largest commercial shipbuilding industry enables China to acquire capital and technical knowledge from foreign contracts. This civil–military integration enables it to build increasingly sophisticated naval vessels and weapon systems. In contrast, the growth of US naval power, epitomised by the aircraft carrier USS Ford, is hamstrung by a dwindling civilian shipbuilding industry. That has led to exorbitant component costs, rendering the USS Ford nearly twice as expensive as the PLA Navy’s smaller Fujian.

A nation’s military capability is determined not only by its defence spending but also by its economic prosperity. In the almost four decades since the opening up of its economy, China has upheld the principle that defence construction must be subordinate to, and serve, the nation’s overall economic goals. Now, Beijing appears to be grappling with an array of challenges, arguably the most comprehensive and daunting since the late 1970s.

These include the repercussions of an inadequate pandemic response, a staggering economic downturn, an immense outflow of foreign investment, steeply rising unemployment, waning domestic market competitiveness, a mounting debt burden, a sluggish real estate industry and a deteriorating trade relationship with the US. If Beijing fails to act promptly, its ability to sustain high defence spending may be limited by a deteriorating balance sheet.

In the meantime, shifting demographics characterised by an ageing and declining population threaten long-term growth. A shrinking labour force and the loss of human capital will further weaken China’s international comparative advantage, making it less appealing for industrial contracts.

The world’s second-largest economy is beset with systemic problems and competing priorities that require a sweeping structural overhaul including decentralisation from Beijing to allow local decision-making, extensive redistribution of resources from the state to the private sector and significant political reforms. The Chinese Communist Party’s reluctance to cede authority makes such a transformation difficult in the extreme.