The Chinese Communist Party is notorious for obscuring how it runs the government of the People’s Republic of China. Its defence budget is particularly murky, earning a measly 1.5 (on a 12-point scale) from Transparency International UK. For reference, New Zealand’s defence budget was assessed at 12 and the US’s at 11.

There are only two sources of information on the PRC’s military expenditure: the United Nations’ military spending database and the PRC’s most recent defence white paper. The former presents reported expenditures from 2006 to 2013. The latter covers the same information from 2010 to 2017. These are big-picture numbers only. Unlike, for example, the United States defence budget, which anyone with a computer can bore down 10 layers into and find the unit price for an M-4 carbine, no similar information exists for China’s expenditure.

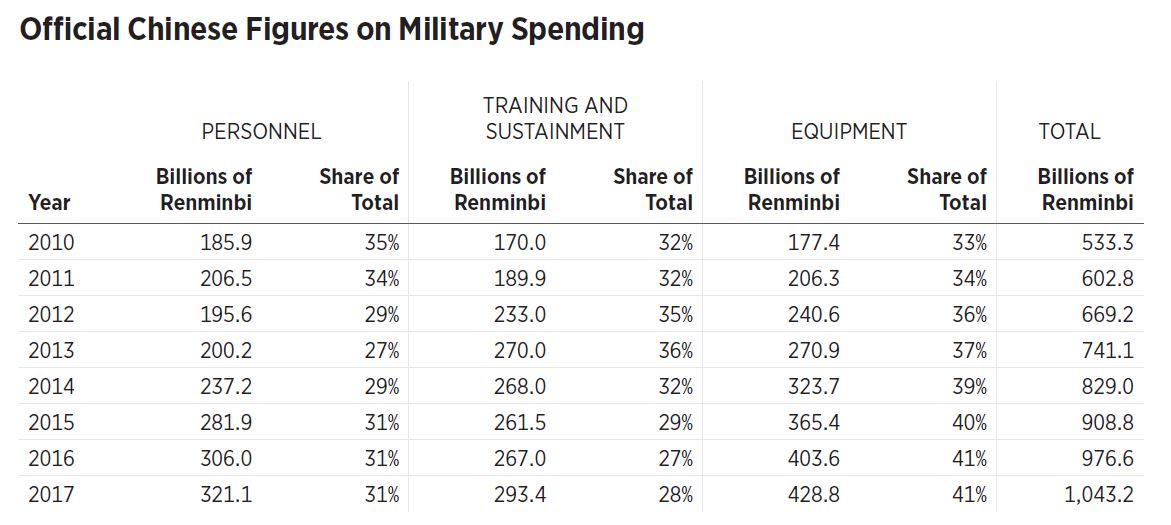

The defence budget data available from Beijing, reproduced in the table below, suffer from three distinct problems: lack of transparency, known omissions and unreliability.

Source: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s national defense in the new era, Foreign Languages Press, 2019, p. 39, accessed 12 February 2020.

Source: State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s national defense in the new era, Foreign Languages Press, 2019, p. 39, accessed 12 February 2020.The data are not very revealing. There are only three big accounts: personnel; training and sustainment; and equipment. And none of the resources are allocated according to service branch, so we can’t see how much of the personnel funds are devoted to the People’s Liberation Army ground forces versus the PLA Rocket Force.

There are also no reported resources dedicated to research and development. This is the largest known omission in the reported budget. The PLA frequently deploys and parades new weapons. They had to be researched and developed somewhere. Adding to the murkiness is Beijing’s embrace of military–civil fusion, which makes it extremely challenging to separate civilian from military R&D.

Other glaring omissions in the PRC’s defence budget are allocations needed to support the People’s Armed Police (now under control of the CCP’s Central Military Commission), foreign weapons procurement, and the subsidies given to state-owned enterprises performing military work.

Neither the UN reporting website nor the white paper has a lot of historical data, starting in 2006 and 2010 respectively. And neither data series is updated to the present, much less able to provide insight as to future plans. Projections based on such limited and unreliable data are but little better than guesswork.

Here’s another problem: the data are reported in billions of yuan, since UN reports are filed with local currency. Distortions arise in any currency conversion, adding to the challenge of understanding what the Chinese numbers mean in nation-to-nation comparisons or in the global context.

The West and its academic community must find a way to overcome all of these challenges if we are to get a clear understanding of PLA military expenditures. There were substantial efforts earlier in the decade, but they have largely dried up.

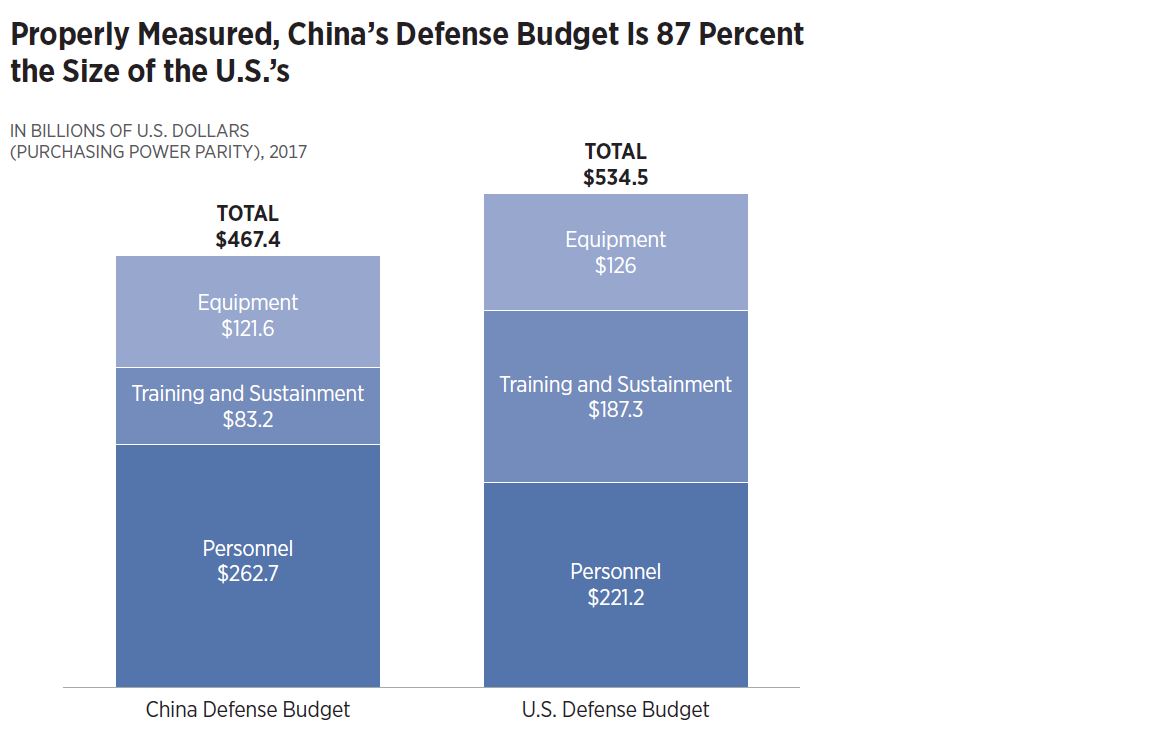

I have taken a shot at comparing how the PRC’s defence budget compares with that of the US. When comparing the two, my goal was to put the US budget in the level of fidelity of the PLA’s. For example, I removed US R&D costs and moved its civilian personnel costs to the personnel account. After those adjustments, the main task was to properly adjust the yuan values to US dollars.

On equipment, training and sustainment values, I used purchasing power parity to give a more equitable comparison. To adjust personnel costs, I compared salaries of all US government workers with those in the PRC to get a multiplier that would make personnel costs equitable.

With those adjustments made to data from the 2017 budgets (the most recent available from the PRC), the PRC’s defence budget accounts for 87.45% of the American purchasing power. This comparison excludes research and development costs. Moreover, because my methodology emphasises the differences in labour costs, it necessarily favours the PRC’s market. The results are displayed in the chart below.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on data accessed on 24 January 2020 from World Bank, ‘PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $)—China’, 1990–2018; National Bureau of Statistics of China, ‘Indicators: employment and wages: average wage of employed persons in state-owned units (yuan)’, 2009–2018; US Bureau of Economic Analysis, ‘Wages and salaries per full-time equivalent employee by industry’, 2011 to 2018; State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s national defense in the new era, Foreign Languages Press, 2019, p. 39; Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National defense budget estimates for FY2020, US Department of Defense, May 2019.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on data accessed on 24 January 2020 from World Bank, ‘PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $)—China’, 1990–2018; National Bureau of Statistics of China, ‘Indicators: employment and wages: average wage of employed persons in state-owned units (yuan)’, 2009–2018; US Bureau of Economic Analysis, ‘Wages and salaries per full-time equivalent employee by industry’, 2011 to 2018; State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s national defense in the new era, Foreign Languages Press, 2019, p. 39; Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National defense budget estimates for FY2020, US Department of Defense, May 2019.Despite its limitations, this comparison should at least draw attention to the gaps in our knowledge of PRC military expenditures. During the Cold War, the US had divisions in multiple intelligence organisations dedicated to understanding the Soviet Union’s military expenditures. That’s not happening with China. Today, Washington’s two authoritative sources on this topic, the US–China Economic and Security Review Commission’s 2019 annual report and the Defense Intelligence Agency’s China military power, dedicated a combined total of five pages to the PRC’s defence budget. Neither report provides any methodological justification for the independent estimates.

The 2017 US national security strategy acknowledges that we have returned to an era of great-power competition. In such an era, understanding what your competitors are doing is essential. Knowing how much your competitors are dedicating to defence is one small part of the puzzle—but it’s an important piece, and one that is currently severely neglected.

We must dedicate more to this discussion if we are to fully understand what the CCP is doing internationally and how the PLA is evolving.