In part 1, I suggested that a defence funding line based on 2% of GDP is likely to fall short of the fixed funding line presented in the 2016 defence white paper. If a future government sticks to 2% of GDP rather than the white paper line, the Defence Department would take a substantial funding cut.

That would be strategically risky for a number of reasons. ASPI has argued (chapter 6) that the future force, much of which won’t be delivered until after 2030 anyway, is probably already unaffordable under the white paper’s funding model. And while the government has so far delivered the funding promised in the white paper, Defence has had to do more with that money. It has had to absorb its share of the Pacific step-up, for example. And the world isn’t getting any safer. Whatever their positions on the future of the US in the Pacific and of the Australia–US alliance, almost all strategic analysts agree Australia needs to be more self-reliant, which comes at a greater financial cost.

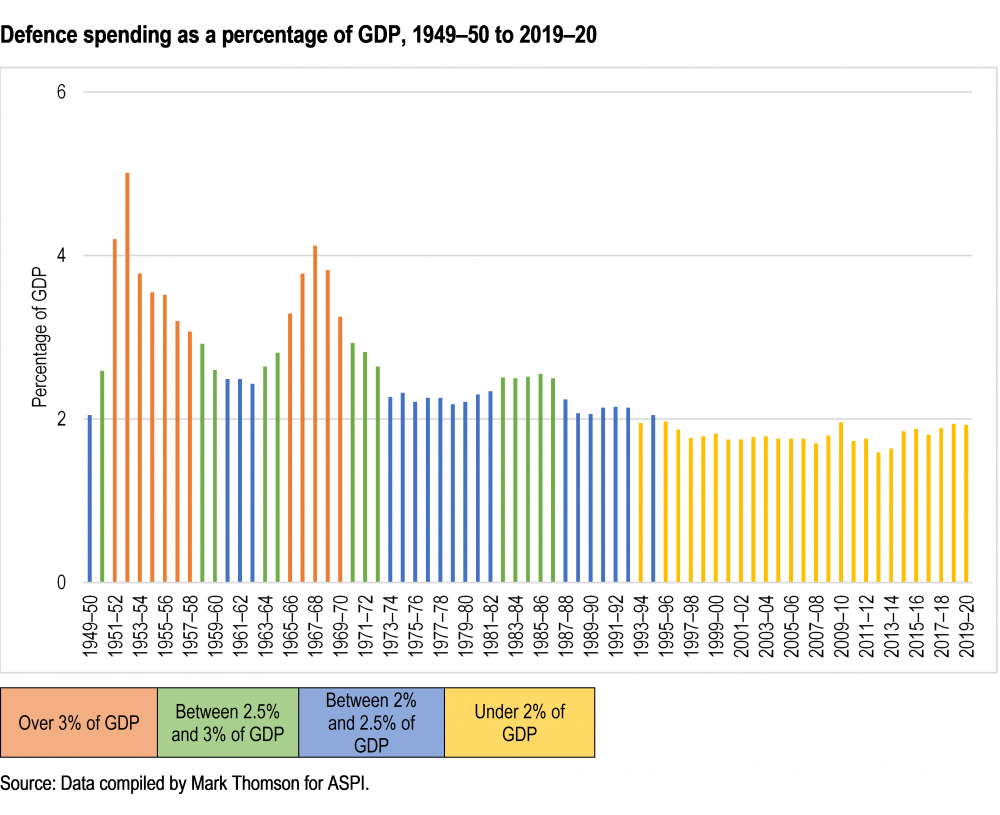

This brings us to the second problem with the 2% benchmark. Some of the discussion of the government’s statements suggests that 2% is a virtually unprecedented peacetime commitment, or at least substantially different from the recent past. The government frequently says that, under Labor, defence spending fell to 1.59% of GDP in 2012–13, the lowest percentage since 1938–39. While that statement is broadly correct, it lacks context.

In fact, 2012–13 was an exception for the government of Kevin Rudd/Julia Gillard as it sought (unsuccessfully) to get the budget back into surplus. Average defence spending under the Rudd/Gillard government was 1.77%—essentially identical to the average of 1.78% during John Howard’s years as prime minister. For all the talk that the Howard government funded a defence build-up—supposedly in response to the Timor crisis revealing serious shortcomings in defence force capability, particularly power projection—it inherited a defence budget of 1.97% of GDP and left it at 1.70%. Even after Timor, the Howard government’s defence spending averaged only 1.76% of GDP (see graph below).

This is not an argument about whether one side of politics is better at funding national security than the other. Over the two decades following the end of the Cold War, both were able to harvest a peace dividend as the world experienced the brief window of ‘the end of history’, where the United States’ power was unchallenged. This started under Bob Hawke’s and Paul Keating’s prime ministerships (when spending declined from around 2.5% to just under 2% of GDP) and continued under Howard’s.

In contrast, Australian governments have consistently spent more than 2% in times of uncertainty and strategic risk. The defence budget was above 2% of GDP from World War II until the early 1990s, in both war and peace, and under both Coalition and Labor governments. During the first half of the 1980s, when Australia was at peace, defence spending averaged 2.5%.

For much of the Vietnam War, the defence budget was over 3%. While we’re not in a shooting war now, it’s reasonable to ask whether the geostrategic risks we’re confronting today are of a similar scale to those we faced in the late 1960s.

So, this government’s commitment to restore the defence budget to 2% of GDP is not a fundamental increase over historical spending, even compared with its immediate predecessors, and it’s less than long-term averages. It’s substantially lower than Australia’s previous spending in times of strategic uncertainty.

Granted, sustained real GDP growth means the economy is bigger, so even with the defence budget fluctuating either side of 2% it has grown in real terms. Which gets us back to the point made in part 1: linking defence funding to a percentage of GDP may make for good slogans, but it’s a crude tool in terms of identifying the resources necessary to address strategic challenges.

Nothing is carved in stone that says defence spending of 2% of GDP will guarantee Australia’s security. Nor is there anything to say that the white paper’s fixed funding line will guarantee our security either. Defence funding needs to be matched to risk. The question is, then, how does the government assess our strategic risks?