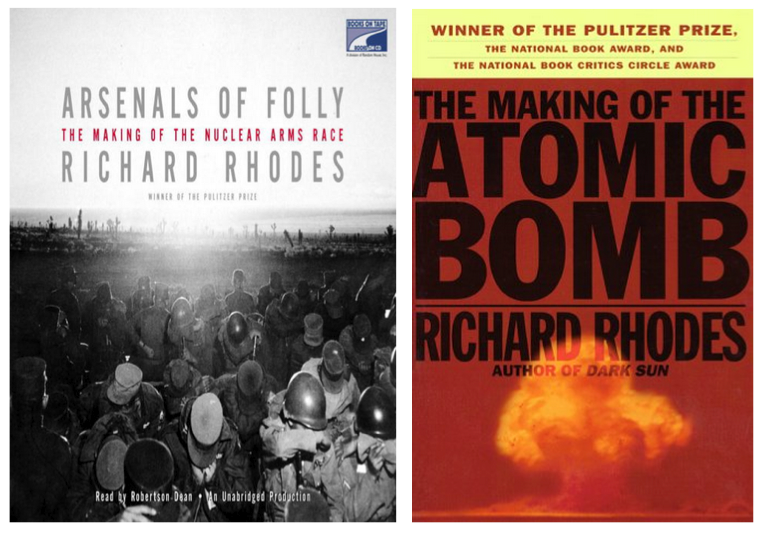

Arsenals of Folly: the making of the nuclear arms race (2007) and The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1986), by Richard Rhodes.

Arsenals of Folly: the making of the nuclear arms race (2007) and The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1986), by Richard Rhodes.

Tomorrow ASPI will publish a short paper by Professor Paul Dibb which describes the 1983 nuclear war scare. (Yes, there was such a thing, and if you haven’t heard this story before, be ready to be surprised by just how dire the situation became.) Later today The Strategist will publish an extract from that paper, and we’ll follow up tomorrow with some reflections on the danger of ignoring nuclear weapons in our current strategic assessments and planning.

After reading Paul’s paper, I went to my bookshelf and pulled down what I think is a pretty good single volume on the evolution of the American and Soviet Cold War nuclear arsenals. Written by Richard Rhodes, Arsenals of Folly was published in 2007 and was the third in Rhodes’ ‘doomsday trilogy’ about nuclear weapons, following books on the atomic bombs of WWII and the hydrogen bomb of the 1950s.

And if you haven’t read it, his previous The making of the atomic bomb is one of the best non-fiction books I’ve read. It should be on the reading list of anyone who wants to understand how pure scientific research translated into the destructive force that drove the Cold War dynamic—albeit only through a prodigious industrial and intellectual effort. It’s also a pretty good primer on physics in the first half of the 20th century and the management of a major project at the absolute cutting edge of science and technology. (Not surprisingly, the Manhattan project was also at the cutting edge of budget and schedule overruns, at 1,500% and 200% respectively.)

Probably the first people to realise the significance of the new weapons were the scientists themselves. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific lead of the Manhattan project, had this to say in 1945:

If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of the nations preparing for war, then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima. The people of this world must unite or they will perish. This war that has ravaged so much of the earth, has written these words. The atomic bomb has spelled them out for all men to understand.

Oppenheimer clearly understood that the new weapons were qualitatively different from anything that had come before, and his intuition was that the only way to avoid a profoundly dangerous arms race—if not a catastrophic war—was not to start it. In other words, the only stable state (as a physicist might term it) is one in which no one has nuclear weapons.

The basic dynamic of the Cold War arms race was foreseen years before by English Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, albeit in the context of air attacks by conventional weapons:

The bomber will always get through… which means that you will have to kill more women and children more effectively than the enemy if you want to save yourselves.

Fear is a very dangerous thing. It is quite true that it may act as a deterrent in people’s minds against war, but it is much more likely to act to make them want to increase armaments to protect them against the terrors that they know might be launched against them.

That, of course, is precisely the trajectory that the Cold War powers took in developing preposterously large nuclear arsenals of 70,000 warheads. The only planning assumption that could be made when facing an adversary with atomic weapons was that they would attempt to use them, and would be successful in delivering them. If that’s the starting point for planning, then the concepts of second strike, counterforce, transattack and the almost ridiculously appropriately named MAD are natural enough developments. But as Rhodes observes, ‘piling up armaments for massive pre-emption or retaliation might deter, but would invite disaster if deterrence failed’. The best you can hope for in those circumstances is what Oppenheimer as a physicist would have called a meta-stable state—something that will hold its form as long as you don’t give it a shove.

Re-reading Arsenals left me with an understanding of why someone like Henry Kissinger, who had been at the heart of the Cold War in successive US administrations, would apparently have an epiphany late in the day and start working against the continued existence of nuclear weapons. As Kissinger and his fellow travellers Sam Nunn, William J. Perry and George P. Shultz wrote recently:

It is far from certain that today’s world can successfully replicate the Cold War Soviet-American deterrence by ‘mutually assured destruction’—the threat of imposing unacceptable damage on the adversary. That was based essentially on a bipolar world. But when a large and growing number of nuclear adversaries confront multiple perceived threats, the relative restraint of the Cold War will be difficult to sustain. The risk that deterrence will fail and that nuclear weapons will be used increases dramatically.

That paragraph still shows a begrudging regard for the detente and management mechanisms that eventually emerged in the Cold War after the excesses of the first couple of decades. In fact, as Paul Dibb will explain, even those elaborate mechanisms almost came disastrously unstuck in a moment of misunderstanding in 1983.

Andrew Davies is senior analyst for defence capability at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist.