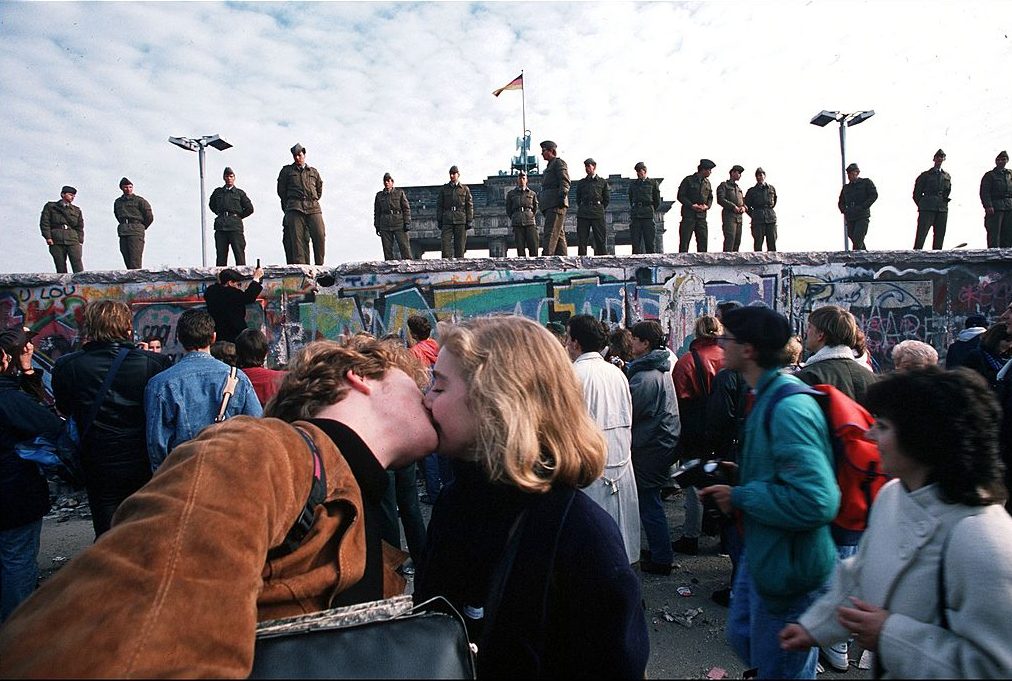

My political awakening coincided with the systemic changes that unfolded following the collapse of communism in Hungary in 1989. I was both fascinated and overjoyed by my country’s rapid democratisation. As a teenager, I persuaded my family to drive me to the Austrian border to see history in the making: the dismantling of the Iron Curtain, which allowed East German refugees to head for the West. Reading many new publications and attending rallies for newly established democratic political parties, I was swept up by the atmosphere of unbounded hope for our future.

Today, such sentiments seem like childish naivete, or at least like the product of an idyllic state of mind. Both democracy and the future of human civilisation are now in grave danger, beset by multifaceted and overlapping crises.

Three decades after the fall of communism, Europe is again being forced to confront anti-democratic political forces. Their actions often resemble those of old-style communists, only now they run on a platform of authoritarian, nativist populism. They still grumble, like the communists of old, about ‘foreign agents’ and ‘enemies of the state’—by which they mean anyone who opposes their values or policy preferences—and they still disparage the West, often using the same terms of abuse we heard during communism. Their political practices have eroded democratic norms and institutions, destroying the public sphere and brainwashing citizens through lies and manipulation.

Nativist populism tends to be geared toward only one purpose: to monopolise state power and all its assets. In my country, Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s regime has almost captured the entire state through the deft manipulation of democratic institutions and the corruption of the economy. Next year’s parliamentary election (in which I am challenging Orban) will show whether Hungary’s state capture can still be reversed.

I believe that it can be. But to hold populists wholly responsible for the erosion of our democracy is to mistake cause and effect. The roots of our democratic shortcomings run deeper than the ruling party’s fervent nationalism, social conservatism and eagerness to curtail constitutional rights. Like the rise of illiberal political parties in older Western democracies, democratic backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe stems from structural issues such as rampant social injustice and inequality. These problems owe much to the mismanagement and abuse of the post-1989 privatisation process and transition to a market economy.

Older, well-established democracies are experiencing similarly distorted social outcomes. With the development of a socially minded welfare state in the immediate post-war decades (a period that French demographer Jean Fourastié famously called ‘les trente glorieuses’), economic growth in Western democracies allowed for a massive expansion of the middle class. But this was followed by a wave of neoliberal deregulation and market fundamentalist economic and social policies, the results of which have become glaringly visible today.

More than anything else, it was the radical decoupling of economic growth from social welfare that let the illiberal populist genie out of the bottle and broke the democratic consensus in many countries.

Even worse, our generation is cursed with more than ‘just’ massive political and social upheaval. We are also facing a climate crisis that calls into question the very preconditions upon which modern societies are organised. Progressives like me see this, too, as a direct consequence of how our economic system works. Infinite, unregulated economic growth—capitalism’s core dynamic—simply is not compatible with life on a planet with finite resources. As matters stand, our capitalist system drives more extraction and generates more emissions every year.

Faced with such challenges, we cannot allow ourselves to succumb to fatalism or apathy. Progressives, after all, must believe in the promise of human progress. Our institutions and economic policies can be adapted to account for changing circumstances. Injustices that alienate people from democracy can be rectified. Channels for democratic dialogue can be restored.

As the mayor of Budapest, a major European city, I can attest to the fact that local governance matters. Whether it is through democratic engagement, emissions reductions or social investment (areas where we have already made significant strides despite fierce resistance from the Orban regime), local governments are well positioned to improve citizens’ lives. And by doing so, we can also create synergies and new models that will contribute to larger-scale progressive change. So, beyond what we do on our own, the city of Budapest is eager to contribute to all international efforts aimed at preserving democracy and a liveable planet.

To that end, we will hold the Budapest Forum for Building Sustainable Democracies this month to bring together a wide range of stakeholders, including mayors, European Union officials, activists and high-profile academics. Participants will discuss strategies for tackling the most pressing policy challenges of our time, and then provide forward-looking, practicable policy recommendations.

As part of the forum, Budapest will also host a Pact of Free Cities summit to build a broader global network of progressive mayors and city leaders who are committed to the defence of democracy and pluralism. More than 20 city leaders—from Los Angeles to Paris and Barcelona to Taipei—are joining an alliance created by the capital-city mayors of the Visegrad Four (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) in December 2019.

Martin Luther King, Jr. said that those who want peace must learn to organise as effectively as those who want war. The same is true of democracy. With the Budapest Forum and the Pact of Free Cities, Budapest intends to help organise forces from all segments of society to ensure a democratic and liveable future in Central and Eastern Europe and beyond. We must win the intellectual fight against nativist populism and the civilisational fight against climate change—and we must do both at the same time.