Australia’s national intelligence agency has released a report that ‘examines the implications of the increasing accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere as a result of the burning of fossil fuels, with special reference to Australia as a producer and exporter of coal’. It flags that ‘major economic and social adjustments’ are going to be required as a result.

Actually, the declassified study, Fossil fuels and the greenhouse effect, was produced 41 years ago by the Office of National Assessments. The timing is right to revisit its findings because ONA’s successor, the Office of National Intelligence, has just completed work on a new classified climate and security risk assessment.

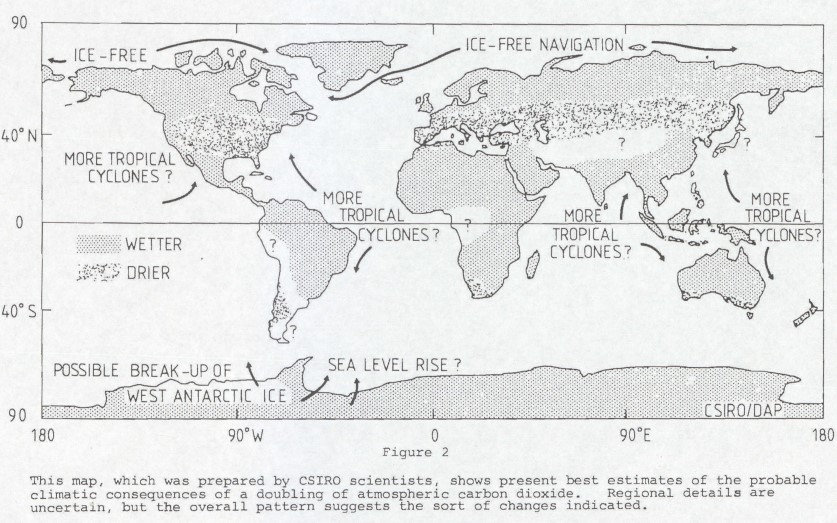

Drawing on the relatively immature climate science available at the time, the 1981 assessment predicted CO2 levels of 600 parts per million by 2050 and 1,200 by 2100. In a series of scenarios, the authors showed how these two- and four-fold increases in CO2 (relative to pre-industrial levels) were correlated with temperature rises of 2°C to 3°C and 4°C to 6°C, respectively. The assessment noted that the level of damage and disruption expected under the 2100 scenario ‘would probably induce international pressure to limit the use of fossil fuels … by the turn of the [20th] century’.

These estimates hold up well. While we are on a trajectory to remain below the CO2 concentrations flagged in the 1981 assessment, the temperature ranges cited were surprisingly accurate. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s most recently published estimates, using a middle-of-the-road emissions scenario, give a 2°C ‘best estimate’ for 2041–2060, and a 2.1°C to 3.5°C ‘very likely’ range for 2081–2100. The most pessimistic and least emissions-constrained scenario canvassed in the IPCC sixth assessment report has a ‘very likely’ range of 3.3°C to 5.7°C by the end of this century.

And while we are not progressing rapidly enough to meet the Paris agreement’s goal of keeping warming below 1.5°C to 2°C, through action to date we may have avoided that most catastrophic end-of-century scenario.

Notwithstanding the often misleading and disingenuous public debate about the state of climate science and uncertainty, it’s worth noting how remarkably consistent the findings of the 1981 assessment and the latest IPCC report are.

The 1981 assessment’s projection of the impacts in 2050 is sanguine, noting there will be benefits and disadvantages in equal measure. In contrast, it describes its more extreme 2100 scenario of 4–6°C of warming as ‘disturbing’ and entailing ‘massive and unacceptable changes’.

Source: Fossil fuels and the greenhouse effect, Office of National Assessments, 1981.

We now understand the regional variation in impacts with much greater fidelity, and the 1981 assessment’s judgement that ‘advanced countries with good scientific, technical and administrative infrastructure’ will be better placed to cope remains valid. Less developed countries are already bearing a disproportionate weight of climate impacts with less capacity to prepare and respond.

But the same multi-disciplinary research that the assessment authors noted was needed and had ‘hardly begun’ in 1981, today suggests a much more pessimistic picture of our global and regional future. Climate change has dire interacting and compounding impacts even at lower levels of warming. We also face the prospect of crossing dangerous thresholds even within the 2°C range of warming.

The 1981 assessment of the energy implications of climate change was less accurate; nuclear power has not emerged in Australia as a pillar of the transition away from fossil fuels. On the other hand, the authors were correct in concluding that solar and wind generation would emerge as the mainstays of the global energy transition.

Bureaucratic understatement was a feature of intelligence assessments then as much as now. The authors summarise the difficult politics and psychology of climate change as a threat: ‘Perhaps because the problem is merely the gradual increase of a non-poisonous substance which has always been present, public alarm will only be generated by manifest change, or a threat of it.’ Indeed.

The assessment itself is evidence of these difficult politics. Delivered to the Coalition government led by Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, the report is, not surprisingly, focused on Australa’s fossil fuel resources. ONA Director-General Michael Cook concludes his executive summary of the assessment by noting: ‘[T]here are potentially adverse implications from these developments (if realised) for the security of Australia’s export markets for coal beyond the end of the next century.’

This judgement has, clearly, held true. The ‘adverse implications’ of these forecasts for coal production are now both unavoidable and necessary. Yet, despite our acute understanding of the severe consequences of further emissions, many still perceive this as only a distant threat. The possibility that natural gas and oil derivatives might supplant Australian coal exports, as suggested in the assessment, has also yet to eventuate—instead, our supplies of both coal and gas dramatically expanded. Globally, the COP27 climate conference in Egypt just concluded without firm agreement on phasing out fossil fuels.

The climate and security work that ONI is now doing has the benefit of drawing on a vast and deep scientific literature and community that were unavailable in 1981. That said, there remains today a relative paucity of work on the societal and economic impacts of the physical changes we know are occurring and deepening.

One lesson we might learn from this four-decade-old publication is the need for greater public discussion about the threat. It isn’t clear if the government intends to publish an unclassified version or summary of the 2022 ONI assessment, but it ought to. As the climate continues to warm in the years ahead, systemic climate impacts, especially in Australia’s near region, will increasingly become one of the key structural determinants of our strategic environment. It would be immensely helpful to know how the Australian national security community is thinking about that challenge. Sharing that information would also be an important step in justifying the extensive work that is going to be required by governments to prepare Australians for the challenges ahead.

If nothing else, we can’t say we weren’t told.