Climate action isn’t just an environmental obligation but is now central to Australia’s diplomatic strategy and national security, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said in a speech at the National Press Club last month.

Albanese’s comments underline the imperative for Australia to step up its regional diplomatic engagement on so-called soft security issues, while also addressing hard security challenges through mechanisms such as AUKUS.

Nowhere is that judgement more relevant than the Indian Ocean region, where Australia and its partners are facing a highly unstable future. In addition to growing strategic competition between major powers, the region faces multiple challenges that threaten its security and stability, including civil conflict, terrorism, piracy, people smuggling and illegal fishing.

But the biggest non‐military threats to regional security will come from climate change and the impact of other human activities on the natural environment.

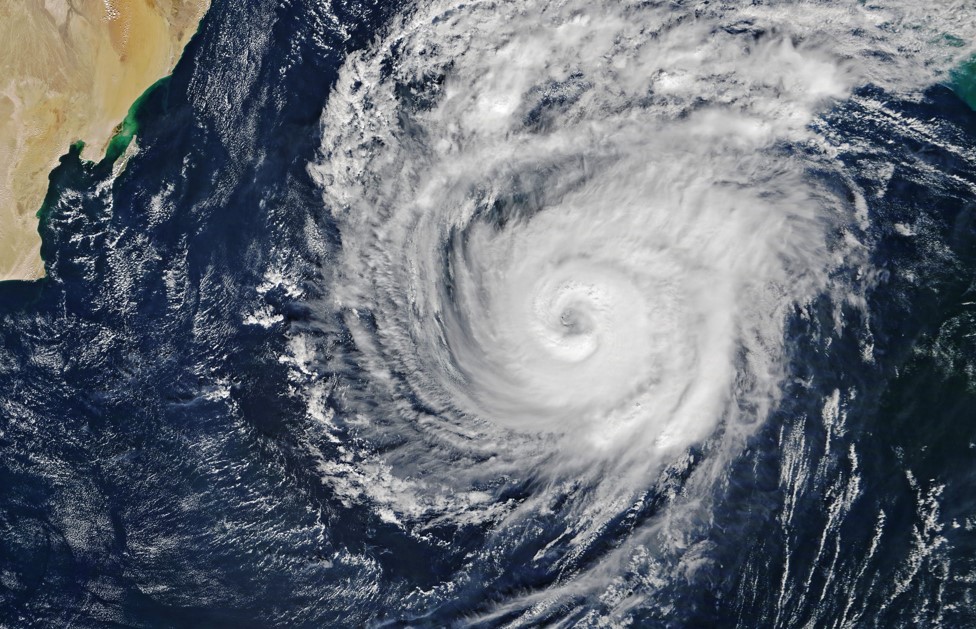

The threats include sea-level rise, severe weather events such as cyclones and storm surges, marine heatwaves, loss of primary producer habitats and organisms due to ocean heating (for example, coral bleaching) and ocean acidification. Shipping accidents, including massive oil spills, also threaten to wreak havoc on island states whose economies are highly dependent on fishing and marine tourism.

These effects are likely to act as multipliers, exacerbating water, energy, food and health challenges that diminish resilience and increase the likelihood of conflict. Sadly, the trend is mainly in the wrong direction.

For many of Australia’s smaller and most vulnerable neighbours, particularly the island states, climate and environmental security threats are their highest priority. For all, it threatens their economic, social and political security, and for some it represents an existential threat. If we want to properly engage with our neighbours, we need to focus on the issues that matter most to them.

Australia should implement a coherent approach to Indian Ocean environmental security as part of an integrated Indo-Pacific strategy. Commendably, Australia has pursued elements of such a strategy with some success in the Pacific, particularly under the Albanese government. But we’re a long way behind in the Indian Ocean, Australia’s often neglected second sea.

It’s no longer good enough to adopt a business-as-usual approach to these problems on our western front. Just as climate change is now a central element in our engagement with the Pacific island states, environmental security should be a key pillar in our engagement with our Indian Ocean neighbours.

Unfortunately, in the Indian Ocean—unlike in the Pacific—there are no effective regionwide mechanisms to facilitate cooperation on policy formulation on climate change or to coordinate responses to different types of environmental security threats. And there’s no reason to believe that groupings in the region will be in a position to take effective action on these issues anytime soon.

The region also lacks an organisation dedicated to advancing environmental security capabilities through professional development for civil and military officials that are responsible for environmental policies and responses. In the Pacific there are regional arrangements that play important roles in professional development in areas such as environmental issues, fisheries governance and law enforcement. But there is nothing comparable in the Indian Ocean.

Our new report, Good neighbours: strengthening environmental security in the Indian Ocean region, makes two key recommendations for Australian-led initiatives in the Indian Ocean.

First, the Albanese government should work with key regional partners to promote an Indian Ocean dialogue on environmental security. This mechanism would include regular meetings at ministerial and senior-official level to develop shared perspectives and coordinate responses to climate change and other environmental security threats.

The dialogue would also provide a platform for Australia and its partners to work together to develop response arrangements for different types of environmental threats ranging from severe weather events to the prevention and mitigation of oil spills and other shipping accidents.

We recommend that just before the senior officials’ meeting, there should be a track 2 meeting of key stakeholders from around the Indian Ocean region and elsewhere, including representatives from academia, science, business and non-government organisations. It would provide a platform for civil-society stakeholders to provide input to the senior officials’ meeting.

The dialogue should start out with key partners such as India and France and other selected countries that prioritise climate action. It would then be built up to include other interested partners.

We also recommend that Australia sponsor the establishment of an Indian Ocean centre for environmental security to provide professional development and training to personnel from civil and military agencies across the region. It might also undertake collaborative applied research on current and projected environmental security threats.

The proposed centre would serve as a knowledge hub and information conduit, including for capacity development in environmental security across the Indian Ocean.

It should receive its core funding from the Australian government, supplemented by funding from key partners. This would demonstrate Australia’s commitment to the region and send a clear message that we are giving priority to the environmental security challenges faced by our partners. The centre should be based in Perth to reinforce the city’s status as Australia’s gateway to the Indian Ocean.

The Indian Ocean region is faced with a wide range of increasing environmental threats. That’s going to require Australia to take a much more active role. We can’t afford to just muddle through when it comes to the security, sustainability and stability of our region.