For well over a century, Myanmar’s remote mountains and valleys have played a central role in the regional supply chains for illicit drugs. Initially, opium poppies were grown in Myanmar; later, high-purity heroin was produced to meet global demand.

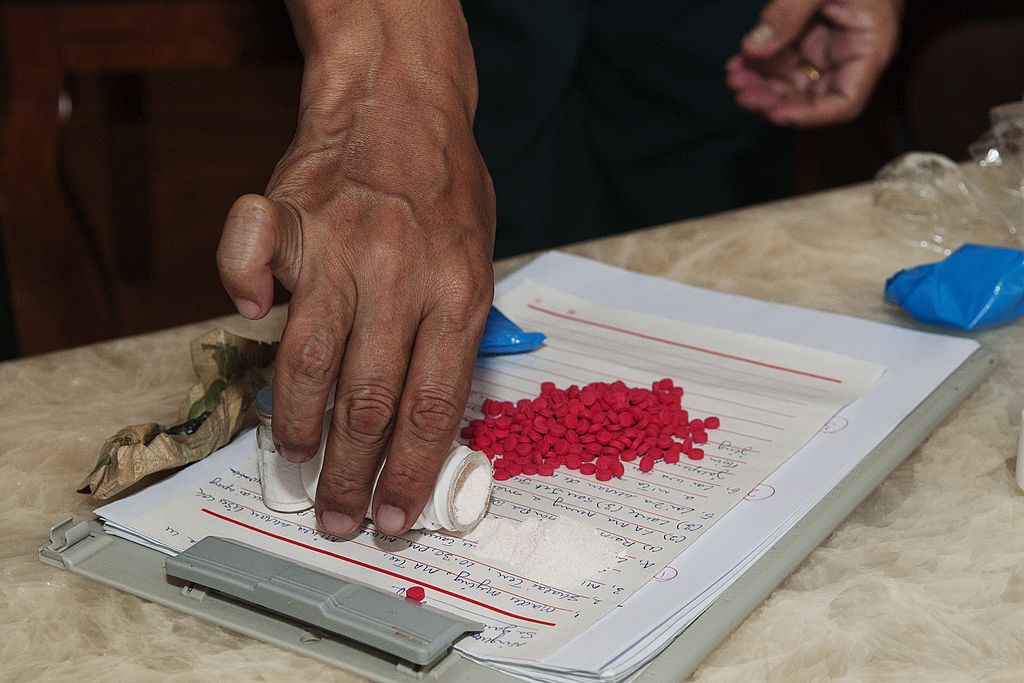

In more recent years, though, illicit drug production in Myanmar has increasingly moved from plant-based heroin to synthetics like methamphetamine. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime World drug report 2017 revealed that criminal groups operating in Myanmar have become significant players in the global production of synthetic drugs.

It’s easy to blame the growing problem of synthetic drug production in Myanmar on ethnic insurgency groups like the United Wa State Army and Shan State Army. However, while these groups are far from innocent, the problem has much more to do with the globalisation of organised crime and the domestic drug policy of the Chinese government. A brief review of Myanmar’s 100-year connection with drug production can shed light on these relationships.

Following the opium wars between China and Britain in the mid-1800s, the demand for opium in China seemed unquenchable. To be fair, the demand was created and then nurtured by the British forcing opium on China rather than by a deliberate Chinese government policy decision.

Opium poppy quickly became a highly valuable cash crop for farmers in Myanmar’s remote hills and valleys.

In 1901, the Chinese Qing Dynasty embarked on a program to suppress the production of opium. While the policy resulted in a reduction in the production of opium in Chinese territory, it drove greater demand for production in the Golden Triangle of Myanmar, Laos and Thailand.

Then, in 1950, the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong, led a nationwide campaign to suppress opium use and production. For a second time, a Chinese government decision would result in a substantial change in regional drug production trends. While this policy decision all but eradicated poppy production in China it again fueled greater production in the Golden Triangle.

By the late 1960s, heroin base was beginning to be produced in Myanmar. By the early 1970s, organised crime groups had established supply chains that stretched from Myanmar to markets in North America and Australia.

By the early 2000s global demand for heroin had peaked, at the same time as production in Afghanistan increased. In contrast, the demand for low-purity methamphetamine, colloquially known as ‘yaba’, was growing across Southeast Asia.

Illicit drug preferences among users in countries like Australia, Canada and the US were also changing. While the demand for plant-based drugs like cocaine and heroin had slowed, there was a growing market for crystal methamphetamine, or ‘ice’.

Meanwhile on the Chinese mainland, economic growth led to a rapid expansion in the number of chemical and pharmaceutical production facilities. This rapid growth—often without adequate controls over illicit drug precursors and industry compliance frameworks—resulted in supply-chain vulnerabilities that were exploited by Chinese organised crime groups.

By the late 2000s, Chinese organised crime groups were supplying much of the global illicit drug markets’ crystal methamphetamine and crystal methamphetamine precursors.

Four years ago, China’s government realised that it had a domestic drug problem. It took swift action and instituted a nationwide crackdown on the production of methamphetamine. For a third time in a little more than a century, the Chinese government’s drug policy would impact on Myanmar.

But this time the production of illicit drugs in Myanmar wouldn’t be controlled by local warlords or criminals. The evidence from organisations like the UNODC appears to indicate that Chinese organised crime groups have relocated their methamphetamine production to Myanmar’s conflict-riddled special zones.

And it’s now a truly transnational organised crime business. Chemists from Taiwan use precursors sourced from Chinese industry to manufacture increasing volumes of yaba and ice in Myanmar to export to global illicit drug markets. Rather than being drug producers, Myanmar’s ethnic armies have become landlords who allow the production and movement of illicit drugs and their precursors.

The key leaders in these global organised crime structures are far removed from the diversion of precursors in China, the production of methamphetamine in Myanmar, the smuggling of illicit drugs across the region, and the money laundering in casinos in Laos.

While the weight and number of seizures across the Mekong subregion continue to grow, the current seizure strategy appears to be unable to reduce the availability of yaba and ice.

Resolving the internal conflict in Myanmar, to reduce the number of ungoverned spaces, is at best a long-term prospect. In the meantime, many an insurgent or militia group in Myanmar is reliant on ‘rent’ from the illicit drug trade to continue its operations.

Stronger methamphetamine precursor controls in China and Myanmar will be critical to any effective response. However, tackling the challenge of methamphetamine production in Myanmar also requires effective regional coordination, that includes the Chinese government, to stem the flow of methamphetamine precursors.

The Mekong Delta’s porous land and water borders makes it difficult to detect and interdict global illicit drug supply chains. Enhancing border management across the Mekong subregion will be critical to disrupting the flow of precursors.

Australia’s strengths in border governance and surveillance could help agencies across the region. There are compelling national security and law enforcement arguments for Australia to do so. As a first step, Australia could focus on encouraging interagency and bilateral information-sharing at border crossings.