Last week we wrote about the transition from the Collins class to the future submarine. Among other things, we pointed out that there’s a tight relationship between the delivery tempo, the maintenance cycle of the boats and the industrial effort required to first produce and then sustain them. We described the effects of the problematic transition from the Oberon class submarines to the Collins in our 2012 Mind the Gap paper. In thinking through the future transition, we now understand the cause: failure was effectively planned into the Oberon to Collins transition, and mismanagement then made it worse.

Probably the clearest way to explain that observation is to work backwards from the current arrangements for Collins maintenance. Outlined in the Coles review into the Collins fleet, the so-called ‘10+2’ arrangement has finally produced a sustainable solution for submarine maintenance—albeit 20 years after delivery of HMAS Collins. It entails ten years between two year periods of major overhaul and refurbishment work (Full Cycle Dockings, or FCDs). In between FCDs there’s a one year mid-cycle docking (MCD) and two intermediate maintenance periods of six months each. So in each 10+2 cycle, a submarine is available for operations for eight years.

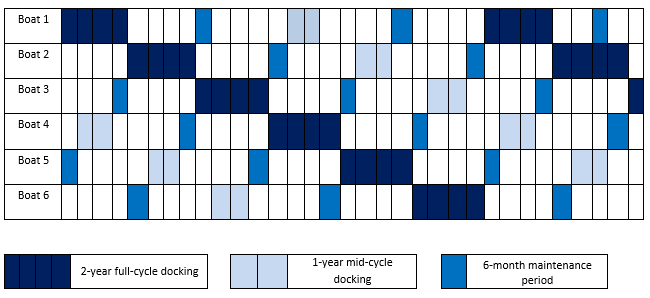

The 10+2 duty cycle is a thing of beauty (figure 1). It sequences Collins support to ensure that two boats are in maintenance at any given time—one undergoing an FCD (in Adelaide) and another undergoing either an MCD or 6-month intermediate docking (in Western Australia). In this model four boats are continuously available for operations, so Navy has a steady availability of sea days to plan training and operations around. And there are two maintenance teams continuously occupied, with no peaks or troughs in workload.

Figure 1: The Coles 10 +2 duty cycle for the Collins in six month time increments

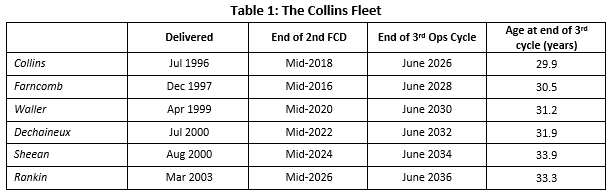

The 10+2 model is being introduced at present. Each of the vessels is scheduled to be delivered from an FCD to begin their third operational period, commencing with Farncomb in mid-2016, followed by Collins in mid-2018 and the other four at two year intervals thereafter. It’s taking some juggling to get to 10+2 because the historical accidents that brought us to where we are means that the FCD dates of the fleet don’t quite line up. Some boats will have to be withdrawn from their second operating period early (HMAS Collins has been out of the water since 2012) or have their current operational period extended a little beyond 10 years (or be out of commission for a while after the 10 years elapses). But the disruption is worthwhile, because it’ll lead to an orderly and sustainable regime for the fleet, culminating in boats leaving service at two-year intervals; Farncomb in mid-2026, Collins in mid-2028, and so on and so forth, see Table 1.

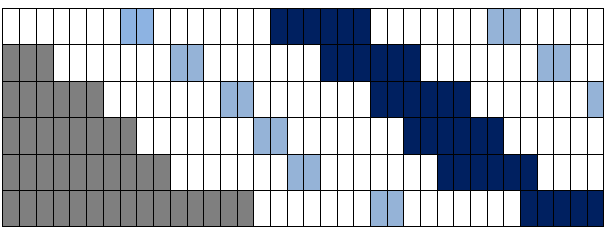

But when the Collins-class was delivered, the plan was for an ‘8+3’ cycle, which couldn’t have delivered anything like the neat arrangement we’ll soon have, especially given the irregular delivery schedule of the Collins program. Using the delivery dates above, the Collins maintenance schedule would have looked something like figure 2 below (we’ve simplified the intermediate dockings a little for this schematic but the point remains).

Figure 2: Schematic of Collins maintenance requirements on ‘8+3’ cycle after initial delivery

As the figure shows, once the series of FCDs begins, eight years after the delivery of HMAS Collins, at various times there are variously one, two or three boats in full- or mid-cycle maintenance. The resulting peaks and troughs in maintenance requirements are difficult to manage. It’s hard and costly to ramp up and down the skilled labour force required to service submarines, and even harder to arrange for additional facilities to be available during surges. It seems likely that this mismatch was a contributing factor to the extended periods some of the boats spent out of the water around the middle of the 2000s. The capability implications were just as dire; even if everything went as planned, at times half of the nation’s submarine fleet would have been offline for a year or more—which in fact happened more than once. The painful experience of the 1990s capability gap and subsequent availability shortfalls under the shambolic maintenance regimen of the 2000s effectively wasted billions of taxpayer dollars.

The conclusion we reluctantly come to is that the Collins program was so poorly planned for through life support after delivery that a substandard outcome was assured even if everything went according to plan (which it didn’t). Getting it right next time will depend on carefully balancing the delivery interval between boats, their subsequent operational and maintenance periods and managing the remaining life in the Collins fleet. We understand that the process to identify the industrial partner for the future submarine requires the bidders to produce a coordinated delivery and sustainment plan. Let’s hope that it all works out—but there are a lot of moving parts to be choreographed.