This year’s Defence White Paper was accompanied by a document entitled 2016 Integrated Investment Plan (IIP) (PDF), which claims to bring together ‘for the first time’ the following:

- Unapproved Major Capital Investment Program

- Approved Major Capital Investment Program

- Major Capital Facilities Program

- Information and communications technology services

- Group and Service workforce plans.

Impressive? Not really. The 2000 White Paper actually employed an even more comprehensive approach (see Chapter 8), which included sustainment. Surely a truly integrated approach would include the more than $8 billion spent annually sustaining the equipment, bases and people of the ADF.

Moreover, the personnel coverage in the IIP simply regurgitates the scarce data already disclosed in the White Paper proper. Even then, the data is of limited use because the personnel baseline remains undisclosed. For example, we’re told that there will be an additional 500 ADF personnel added to the strike and air combat workforce, which is all very interesting. But because we don’t know what the size of the strike and air combat workforce is to start with, we can’t say whether the workforce has increased by 5% or 50%. The result is a series of impressive sound-bites without the context needed to make sense of the changes.

What are we left with? All up, we get a list of 166 planned equipment and facilities projects and a partial list of (34 out of more than 150) pre-existing equipment projects. Only a couple of the current 55 major facilities projects make the cut. We’re told that the IIP contains investment of approximately $195 billion in defence capability over the forthcoming decade. Yet, the explicit annual figures for capital investment in the DWP (see page 182) amount to only $162 billion over the period. I have no explanation for the missing $33 billion. Dibs if it turns up.

The strength of the IPP is that it provides a narrative description of planned investment in each of four adjective-laden categories, including Enabled, Mobile and Sustainable Forces and Potent and Agile Offensive Response. (If you ever want to parody defence-speak, simply ensure that there are at least two adjectives for every noun.) Read in tandem with the 2016 DWP, it provides at least as clear a sketch of overall plans for the ADF as the 2009 or 2013 DWPs. That said; there are more than a few gaps. For example, the need to extend the life of at least some of the Collins fleet only came to light following media investigations several days after the document’s release.

At the project/program level only two pieces of information are consistently provided. The first is the ‘approximate investment value’ expressed as a range such as $100–200 million. Unfortunately, the numbers are given in ‘out-turned’ dollars that include anticipated inflation over the life of the project. For example, the ‘greater than $50 billion’ price for the future submarine reduces to a much more modest ‘greater than $28 billion’ in today’s dollars under reasonable (by though no means certain) assumptions about spending profile. Using out-turned dollars as the sole source of disclosed costs is misleading to the point of obfuscation.

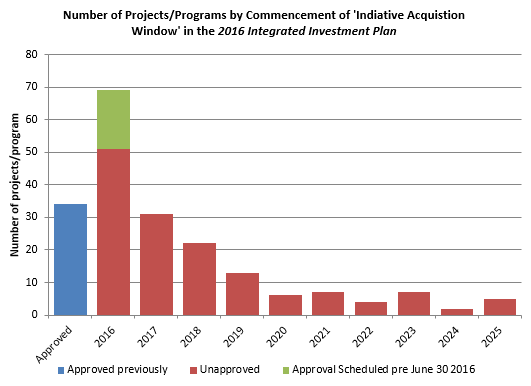

The second piece of information is what’s referred to as either ‘Program Timeframe’ or ‘Indicative Acquisition Window’, depending where you look. For example, the future submarine is given the window 2018–2057. Absent a definition, we’re left to guess its meaning. From the submarine example, we know that the end dates don’t correspond to in-service-dates. From the 69 project windows commencing over the next 10 months (see above), the start dates don’t correspond to project approval—unless the program is preposterously front loaded and impractical. Thus, with neither year-of-decision nor in-service dates provided, the IIP provides precious little useful information about project timing.

To make matters worse, the description of projects is often much less than was previously provided under the Defence Capability Plan (DCP). Take for example the ‘Destroyer Program – Combat System’ valued at $4–5 billion planned for the period 2017–2028. Apart from a commitment to ‘regularly upgrade the AEGIS combat system’ and a reference to ‘upgrades to the destroyer’s and ANZAC Class frigates’ combat systems’, we’re left in the dark as to why we need to spend this prodigious amount on upgrading the combat system on vessels that haven’t yet been delivered and whose core combat system only cost US450 million to buy in the first place. The only explanation that readily comes to mind is that the AWDs are going to be upgraded to support Ballistic Missile Defence, though Japan upgraded the AEGIS combat systems on two of its vessels in 2012 for only US$421 million. In any case, it would be extraordinary if so strategically sensitive an enhancement wasn’t carefully explained in the White Paper. Who knows what’s going on?

In conclusion, despite its many colourful charts and self-congratulatory ‘for the first time’ claim, the level of disclosure in the IIP is below that of DCP published from 2001–2012, and even compares poorly with the public ‘Pink Books’ and ‘Green Books’ of the 1990s. As a result, the 2016 IIP represents the lowest point in defence capability planning transparency in a quarter-century.

Lest it seem that I’m being critical without being constructive, here’s a link to a report (PDF) I co-authored for the government back in 2010 on how to disclose capability planning information consistent with security and commercial considerations. Transparency matters because it assists industry to plan and allows the government and Defence to be held to account. With major reforms underway in the areas of capability planning and acquisition, and with industry now being identified as a ‘fundamental input to capability’, we need more transparency not less.