Scarcity of food and energy is a growing problem due to the effects of climate change. Some arid areas may run out of water and food.

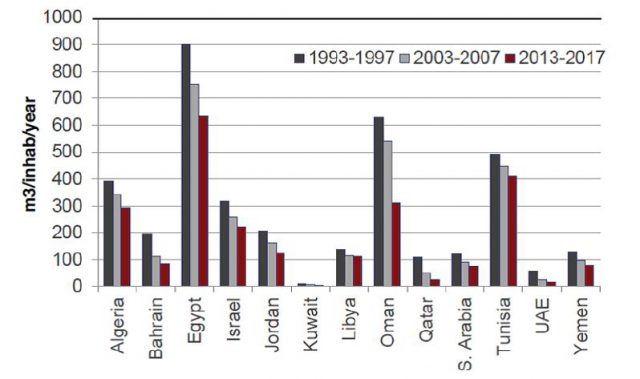

The graph above shows per capita water supply in water-stressed countries and highlights the decrease in available water. The line at the top of the figure represents the UN’s water poverty line; many of these countries are already in an extreme situation. NASA has also just released this scary report on global water.

These stressors are all part of the broader issue of the effects of a changing climate on national security. So the Australian Senate’s Foreign Affairs, Trade and Defence Committee’s recently tabled report on the implications of climate change for our national security is timely.

The committee considered the long-term risks that climate change poses to national and international security; the role of humanitarian and military responses in addressing climate change; the capacity and preparedness of our security agencies to respond to climate change risks in our region; the role of our overseas development assistance in climate change mitigation and adaptation; and the role of climate mitigation policies in reducing security risks.

Three of the committee’s 11 recommendations relate directly to the Department of Defence. Rather than review all of the report’s findings and recommendations, I’ll offer some brief comments on each of the three Defence-specific recommendations.

Recommendation 4: The committee recommends the Department of Defence consider releasing an unclassified version of the work undertaken by Defence to identify climate risks to its estate.

Most current defence infrastructure was built on the assumption of a stable climate with predictable variability, but many naval facilities, bases and dockyards are built in low-lying areas exposed to storm surges and sea-level rise.

The committee’s recommendation is in line with Australia’s 2016 Defence White Paper, which noted the pressure that sea-level rises and more severe weather events will put on the defence estate, including the implications of storm surges for navy bases.

The white paper expressed the need for Defence to be appropriately postured to meet the implications of climate change and how those threats should be considered when developing new bases, wharves, airfields, and training and weapons testing ranges, as well as in considering the long-term future of some Defence bases, such as Garden Island in Sydney Harbour.

The Senate committee’s recommendation on the defence estate is sensible. It’d be helpful—especially for other agencies at the local, state and federal levels that are involved in climate mitigation and adaptation—to know what work Defence has done to identify climate risks to its very large estate.

Recommendation 7: The committee recommends that the Department of Defence create a dedicated senior leadership position to assist in planning and managing the delivery of domestic and international humanitarian assistance and disaster relief as pressures increase over time.

The committee is right to point out that the increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events will have implications for Defence’s humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) missions.

Many of the poorest countries in the world lie in the areas of the Pacific and Indian Oceans where cyclones and typhoons are most prevalent. The resulting destruction from these extreme weather events will place more pressure on the ADF to provide HADR.

The committee’s report reproduces a very useful figure (provided by Defence in response to a question from the committee) that shows the increased Defence role in HADR.

HADR operations are likely to be increasingly addressed in ADF training, exercises and doctrine. A number of ADF assets can be easily adapted for such responses, including the amphibious ships HMAS Canberra and HMAS Adelaide. The Indo-Pacific region is regarded as the most disaster-prone region in the world, and HADR has become a central part of military doctrine for regional countries.

In mid-2016, Defence usefully appointed a reserve colonel as a climate and security adviser to raise awareness of climate change across the Defence organisation. But establishing a dedicated senior Defence leadership position to assist in planning and managing domestic and international HADR would be a sound investment.

I’d also suggest that the position should have a broader responsibility to act as a strategic voice for defence-related climate change issues, including preparedness and capability. Interestingly, the committee also recommended that a climate security role be created within the Home Affairs portfolio to oversee domestic responses to climate change.

Recommendation 10: The committee recommends that the Department of Defence establish emissions reductions targets across stationary and operational energy use, and report against these in its annual report.

Modern warships and high-performance military aircraft, in particular, have very high rates of fuel consumption. There’s the potential for the ADF to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by its vehicles, ships and aircraft and to use more renewable energy.

Setting internal emissions reduction targets for Defence would demonstrate that the organisation is prepared to be a responsible stakeholder (Defence is the Commonwealth’s largest emitter). But generally speaking, moves to reduce non-operational emissions by using renewables probably offers greater potential for military bases than for military vehicles, ships or aircraft.

A good example here is Defence’s contracts with Carnegie Clean Energy to build microgrids at Bathurst Island and the Delamere weapons range base in the Northern Territory and to supply power and water to the country’s largest naval base, HMAS Stirling, in Western Australia. HMAS Stirling is powered by the world’s first grid-connected wave power station that also supplies zero-emission desalinated water.

Defence will be a key stakeholder in the Australian government’s inquiry into liquid fuel security that will presumably examine the place for alternative energy sources. The inquiry was announced just over a week before the Senate report was released.

Sensibly, there’s no suggestion in the committee’s report that Defence should be the lead agency for managing the national security impacts of climate change. But what comes through loud and clear in the report is that ADF doctrine, plans and strategy will need to consider projected climate impacts.