Singapore and Australia have nothing in common but share much. No similarities, yet multiple places where interests and attitudes touch or chime.

Geographically, they are mismatched mates: the nation with a continent to itself shares a chinwag with Asia’s city state. It shouldn’t work—but often, it does.

I’ve lived and worked in Singapore and have been visiting for decades so this view may merely reflect my comfort levels. Love the heat. Know the people. Enjoy the place—although I’m always amazed at how they constantly demolish and rebuild.

The mateship is defined by the mismatch, but it can still be analysed as a long-term relationship. After Lee Kuan Yew died in March, this column argued that a useful history of Australia’s apprehensions and aspirations in Southeast Asia over the last 75 years could be written using LKY as actor and commentator. A previous column looked at Singapore on its 50th birthday this month, which leads to these thoughts on the strange mates.

What do they have in common? Some traces of colonial experience—political and legal forms—but mostly English as the shared international/regional language. After that…zip. Well, zero common characteristics which are natural or obvious. The contrasts between the continent and the city state can confound.

What Singapore and Oz share aren’t characteristics so much as attitudes. And a strategic cast of mind emphatically expressed in the approach to the United States. Who loves the US hegemon more? It’s impossible to separate the mates in their affection for the US and the 7th Fleet.

A shared obsession with Indonesia matters as much. This isn’t a mirror of the US fixation because the colours are so different. With Indonesia, the apprehension is shaded by differences and tinged by fear. Indonesia always gives Singapore and Australia something to talk about.

The odd couple obsess constantly about China, but Singapore brings a Confucian cast of mind that Australia hardly grasps. China is a stark example of the mates staring at the same thing using the same data but different understandings.

The political cultures of Singapore and Oz are worlds apart, yet one single, shared element throbs strongly. These are two intensely pragmatic operators. Rely on Australia to call a spade a bloody shovel, while Singapore will know the cost of the digging implement and the necessary size of the hole required.

For a taste of the Singapore style, see the Shedden lecture in Canberra by Singapore’s Ambassador-at-Large, Bilahari Kausikan:

- Don’t deny strategic ambiguity, embrace it

- To be forced to choose is to have failed

- US–China competition gives the rest of us room to move—especially because Washington and Beijing don’t really know what they want

For Singapore, ASEAN is core business and a vital element of its existence; Australia’s interest in ASEAN is nearly as heartfelt. Australia says Southeast Asia is currently more important than at any time since the Vietnam War. The small mate responds that its region is as important as ever and growing fast—sometimes, Singapore thinks, the big mate is a bit slow or takes his eye off the main game.

The pragmatism of the language between Australia and Singapore is a constant. The arguments are forceful rather than emotional. Very forceful in the clash—ego and intellect—between LKY and Gough Whitlam.

Mostly, though, it’s about the usefulness of the shovel. Singapore kicked to death Kevin Rudd’s proposal for an Asia Pacific Community.

And having won, Singapore rushed to reassure Canberra that it was only business, nothing personal.

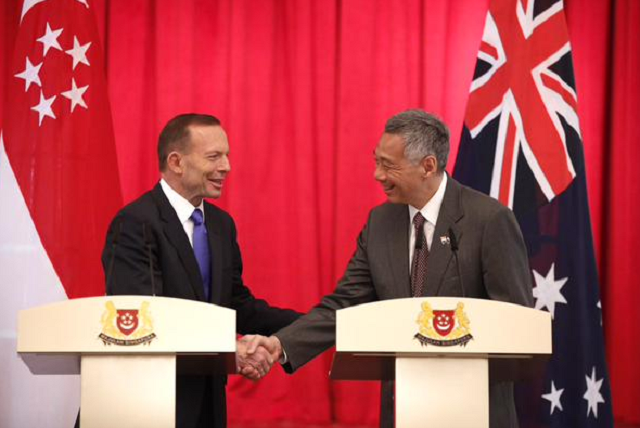

The pragmatism and the shared interests throbbed in every line of the joint presser when Tony Abbott and Lee Hsien Loong met in Singapore in June to announce a Comprehensive Strategic Relationship.

Partly, the Comprehensive and the Strategic stuff was about rebadging and pushing much that already exists, as Lee made clear:

Beyond interest, there is also a special warmth in the relationship because of our temperaments of our national ethos, because of our preference to be direct and straight and candid and to the point, and informal, and that applies whether between our politicians, our institutions and our peoples. And so with our strategic convergence and our many complementarities, it is not surprising that there are many ways we can work more closely together.

The backslapping and glad-handing which must accompany such performances—the ‘transformational’ agreement etc.—rests on the mate base. Perhaps Abbott and Lee could share a private moment discussing the problems a leader has in moving beyond the shadow of a strong political mentor/father predecessor.

The tone of the Lee-Abbott presser, though, could be replicated in previous conversations between LKY and Malcolm Fraser or Bob Hawke. The same for Goh Chok Tong with Paul Keating or John Howard. The Lees, father and son, and Goh are three markedly different personalities. Say the same, emphatically, for Fraser, Hawke, Keating and Howard.

History offers evidence that the mates usually talk directly and openly. For Oz, however, that isn’t always the case with Indonesia, Malaysia or Thailand. An Oz conversation with the Philippines puts the ‘free’ into free-wheeling, but the ups-and-downs of Manila are an American-tinged contrast to the political predictability of a one-party city state.

In Singapore, the guy in power last year is the guy in power today, and will be the one in power next year. Three leaders from the one party in 50 years delivers a certain comfort. In the strategic realm, that translates as continuity. Pragmatists value predictability.

The Oz–Singapore history makes it uncontroversial for Abbott to aim to turn friendship into ‘a family relationship’—to see beyond mateship to a form of kinship.

Abbott is stretching for the same work and residency rights with Singapore as have long existed with New Zealand. The Kiwi analogy fits on the level of ‘bloody shovel’ pragmatism—we’ll just have to create some Singapore jokes to match the mould.